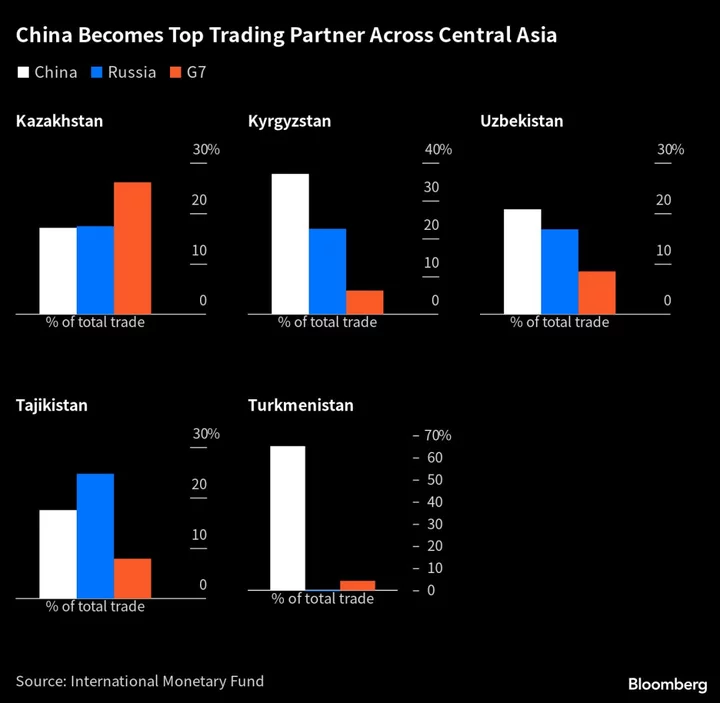

An economic seesaw between China and Russia in Central Asia is moving toward a new equilibrium for Kazakhstan, which expects its eastern neighbor to come out on top as international sanctions over the Kremlin’s invasion of Ukraine transform commerce.

In the over three decades since the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia held on to its spot as the biggest trading partner for Kazakhstan even as China made inroads across much of the region that stretches from the Caspian to Manchuria.

But financial and economic sanctions that have sidelined Russia and diverted trade flows are creating an opening for China. Serik Zhumangarin, Kazakhstan’s deputy prime minister and its minister of trade and integration, said it’s a matter of a few years before China overtakes Russia.

“The growth in trade is happening due to China,” he said in an interview in the capital, Astana. By 2030, Zhumangarin expects volumes with China to eclipse Kazakh trade with the 27-nation European Union as a whole.

For centuries a gateway for China’s trade with Europe and the Middle East, Central Asia is now at the nexus of competing interests spreading from Washington to Moscow and Beijing.

China’s President Xi Jinping last year chose Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan for his first foreign trip since the coronavirus pandemic. The US and the EU have also stepped up their outreach.

But while countries from Italy to Australia rethink their ties with China, the pull of the world’s second-biggest economy may prove hard to resist for the nations of Central Asia, which also include Turkmenistan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan.

Trade with China surged by about a third last year to approach $24 billion for Kazakhstan. It still lagged volumes with Russia — which added just over 6% in 2022 — by about $2 billion, according to Kazakhstan’s Bureau of National Statistics.

President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, a Mandarin speaker who once worked as a diplomat in China, has refused to side with Russia over the invasion launched just weeks after he needed troops sent by President Vladimir Putin to crush deadly riots in early 2022.

But even as Kazakhstan has said it’s complying with the curbs imposed in punishment for the war, it opposes the US-led campaign of sanctions and has seen trade with Russia grow since the attack on Ukraine in February 2022. Along with countries like Turkey and the United Arab Emirates, Kazakhstan has been under scrutiny by western governments for facilitating shipments of restricted goods.

Outside the Perimeter

“We aren’t within the perimeter of the sanctions and we do not support them, especially against our main trading partners,” Zhumangarin said. “But we comply with these sanctions and will continue to comply. And this is purely economic policy.”

The world’s largest landlocked country is the biggest global miner of uranium and a top producer of commodities such as ferrochrome. Transit is like “fresh air” for Kazakhstan’s mining and metallurgical industries, Zhumangarin said.

For Kazakhstan, Russia was long an outlet to the outside world, enabling maritime access and creating an entry point into a much larger market thanks to low trade barriers and established supply lines.

The two countries are members of a customs union and share the world’s second-longest frontier after the US-Canada border, with a pipeline linked to the Russian port of Novorossiysk transporting about 80% of Kazakh oil exports.

The calculus for Kazakhstan is changing after the invasion.

The movement of goods through Russia has become more difficult and some of its sanctioned companies could no longer receive Kazakh raw materials, Zhumangarin said. And as more Russian producers focus on the domestic market, they’re crowding out Kazakh exports, he said.

Though overall trade with Russia last quarter was up 10% from a year earlier, according to Zhumangarin, the ripple effects of sanctions have forced Kazakhstan to adjust by starting to re-export more goods and building up local production.

As trade opportunities narrow with Russia, Kazakhstan is looking east to China and across the Caspian to Iran — and then to the Gulf region, India and beyond. “The Chinese direction is a priority,” Zhumangarin said.

At last month’s meeting with Xi — during the first in-person summit of Central Asian leaders in China — Tokayev set the goal of nearly doubling trade with China to $40 billion by 2030.

Chinese companies have already started to assemble vehicles in Kazakhstan, which expects other auto brands like Chery to follow soon, Zhumangarin said.

Kazakhstan has meanwhile started to ship grain to China and is now in talks to export meat there. In addition to two existing rail terminals linking Kazakhstan with China, it’s building another and plans a fourth link, Zhumangarin said.

China has also taken interest in a trade corridor that runs through Kazakhstan from Southeast Asia to Georgia in the Caucasus, creating a springboard to reach European countries. The trans-Caspian transport route would accommodate some goods diverted from Russia along with additional trade traffic, according to Zhumangarin.

Now that Russia is no longer a destination for some Kazakh products, it’s working to diversify supplies with shipments of iron ore to China and talks to start its supplies to Europe, Zhumangarin said.

Fearful of getting caught up in sanctions, Kazakhstan must thread a needle.

“If Kazakhstan comes under sanctions, it may simply not withstand the pressure,” Zhumangarin said. “Kazakhstan won’t be a territory through which sanctions are bypassed.”