China has passed a sweeping foreign policy law that bolts together a slew of existing tools to counter Western powers, and extends President Xi Jinping’s combative stance on asserting Beijing on the world stage.

Enacted with the stated intention of safeguarding China’s national security and development interests, the Law on Foreign Relations stops short of creating new mechanisms for responding to rising geopolitical challenges, such as US-led export controls on advanced technology.

Instead, the umbrella legislation gives Beijing’s existing toolkit more weight by embracing it in a legal document alongside two of Xi’s signature foreign policy initiatives. Both the Global Security Initiative and Global Civilization Initiative are baked into the law, approved by the standing committee of the National People’s Congress on Wednesday.

The US has singled out a range of Chinese companies and officials with sanctions, accusing them of involvement in human rights abuses that China denies. Last October, the Biden administration also tightened restrictions on US microchip exports to China — controls the Biden administration is now considering strengthening further.

China is refusing to resume high-level communication with American armed forces until Washington lifts sanctions on Chinese Defense Minister Li Shangfu.

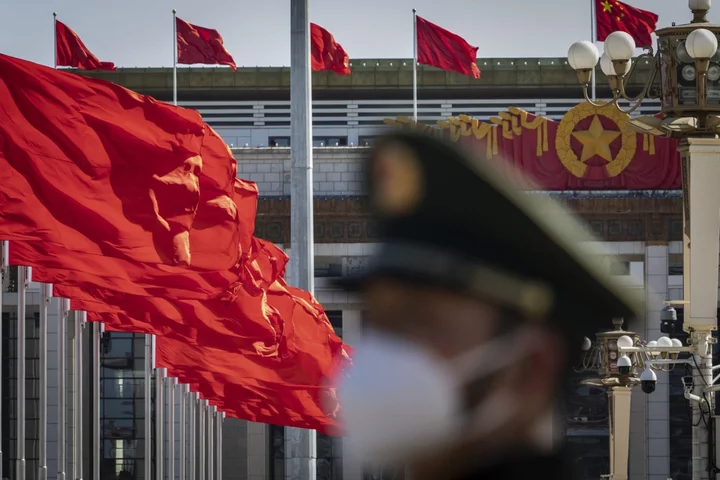

While the law is directed at government agencies, it states the conduct of foreign relations falls under the leadership of the Communist Party. Xi has enhanced the party’s grip on government bodies in recent years as he consolidates power in the world’s second largest economy.

China’s top diplomat, Wang Yi, called the law “an important measure to strengthen the Communist Party Central Committee’s centralized and unified leadership over foreign affairs,” in an editorial Thursday in the Communist Party mouthpiece People’s Daily.

Suisheng Zhao, a professor at the Josef Korbel School of International Studies, University of Denver, said the document is more like Xi’s foreign policy declaration than a new legislation.

“It’s a personalization of Chinese foreign policy through a legal process,” said Zhao. The law “makes so clear that the party is in charge of foreign policy, and the foreign ministry and State Council is the implementing institution.”

Blunt Tools

Xi has struggled for years to find a response to US sanctions, tariffs and export controls that makes China look tough without scaring off foreign companies. While Beijing has developed an “unreliable entity list,” an anti-foreign sanctions law, and Hong Kong’s national security law, they haven’t been used to any meaningful degree.

Beijing’s decision earlier this year to put Lockheed Martin Corp. and a subsidiary of Raytheon Technologies Corp. on the entity list, for example, was largely symbolic: The two US defense contractors don’t have significant business in China.

China’s most meaningful action came last month, when it banned domestic operators of key infrastructure from buying Micron Technology Inc.’s products, a cautious move as replacements for the company’s memory chips are easily sourced from local suppliers.

Beijing has also sanctioned individuals, including former US Secretary of State Michael Pompeo in recent years, who have few, if any, ties to the Chinese economy.

Further signaling the challenges facing Xi in responding to US curbs, China’s top legislative body has postponed a proposal to impose an anti-sanctions law on Hong Kong. Business leaders in the finance hub raised concerns the law could allow Beijing to seize assets from entities that implement US sanctions. Financial institutions in Hong Kong are reliant on the dollar and comply with US sanctions.

Beijing has similarly avoided violating US sanctions over Russia’s war in Ukraine, wary of blowback on its own economy and companies.

Deeper Coordination

The law calls on state agencies charged with executing Xi’s vision to strengthen interdepartmental coordination and cooperation to enforce retaliatory measures. The State Council, which co-ordinates China’s government ministries, is authorized to “establish related working institutions.”

The legislation has a range of other clauses, some of which also echo existing regulations. It requires foreign nationals and organizations in China not to endanger the country’s national security, undermine social and public interests or disrupt social and public order.

It also adds that China is committed to “high-standard opening-up,” protects inbound foreign investment and encourages external economic cooperation. That echoes regular pledges from Xi and Premier Li Qiang that China remains open to overseas business.

(Updates with details throughout.)