Legal and regulatory hurdles for people offering their homes for short-term rental on sites like Airbnb Inc. and Vrbo are upending the market for vacation properties.

From New York to California, cities are cracking down on short-term rentals with bans, license requirements or limits on how many people can offer their homes for stays of 30 days or less. Airbnb and property owners are fighting back in court, but their lawsuits so far have had little success.

Many restrictions were imposed just as cities were recovering from the pandemic. They are helping reshape the market and in some places, making it harder for hosts to list their properties — taking away a steady stream of secondary income from property owners.

“There’s this assumption that only rich people are making money off multiple Airbnbs, but it’s average people like me that depend on short-term rental incomes to sustain their lives,” said Lisa Cameron, an Airbnb host who got hit with a $500 fine. “It’s not fair, and there has to be a happy medium.”

Cameron offered a 400-square-foot studio she owns in Santa Rosa, California, for more than a decade. The city recently required permits for those offering stays of 30 days or less and capped the number of permits. Cameron says she wasn’t properly notified of the new rules, and in February got a violation notice. On top of the fine, the city banned her from any new bookings until she gets the proper permit.

Getting a permit was not only expensive, but also hard to obtain because the city put a cap on how many can be issued, Cameron said, adding that the income she’d been using to help build her private-chef business dropped from $5,500 a month to zero.

Increased Regulation

Cities want more rules because they claim unregulated short-term rentals reduce the availability of affordable housing, boost local rents and create unnecessary risks for guests and neighbors.

Property owners are pushing back in court, arguing the regulations violate their constitutional rights. The new rules are being challenged by hosts across the country, including cases filed in Kansas City, Santa Fe, New Mexico, and Fort Worth, Texas. These suits may take years to resolve.

Airbnb and three local hosts tried to fight New York in court, arguing the city’s law requiring operating licenses imposes “massive burdens” on booking services and forces hosts to navigate “labyrinthine” municipal regulations. A judge tossed the New York case in August, and the ordinance, which Airbnb described as a “de facto ban” on short-term rentals, will go into effect in September.

Airbnb said that approximately 80% of its 200 markets by revenue around the world already have some type of regulation in place, and that internal company data do not show a drop in the typical earnings or nights booked after regulations were put in place in Santa Rosa. Vrbo didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment.

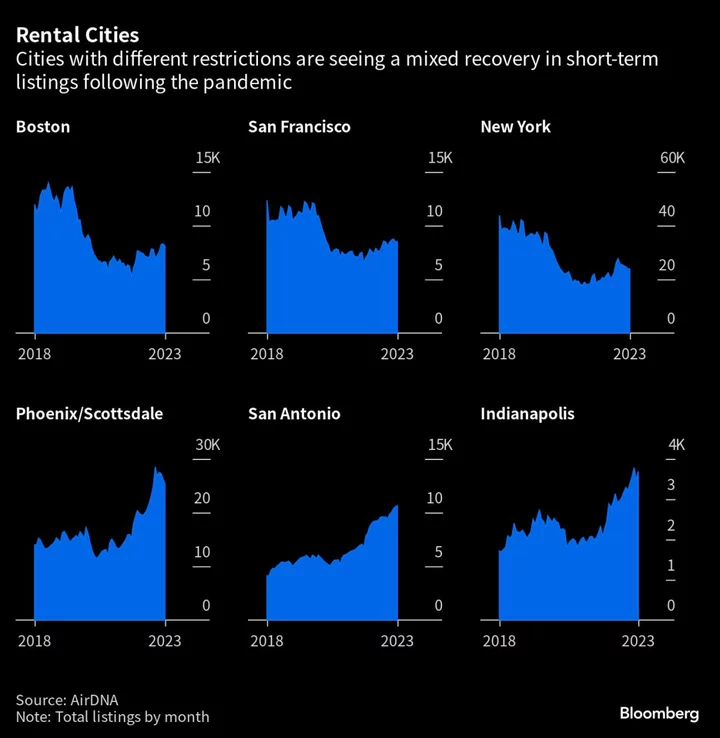

The demand for short-term rentals tumbled in many big cities during the pandemic, as offices shuttered, travel was restricted and remote workers hunkered down at home. While demand has been recovering, some cities that imposed tighter rules still remain below where they were before Covid, according to researcher AirDNA, which tracks data from Airbnb and Vrbo.

In New York, listings were down 39% in July, compared with the same month in 2018, according to AirDNA. Boston, which imposed stricter rules in 2019, saw a similar drop. In San Francisco, short-term rentals fell 19%, data show.

Meanwhile, hosts in cities with fewer regulations are exceeding pre-pandemic levels. Short-term listings in July doubled in San Antonio, compared with the same month in 2018, while the Phoenix-Scottsdale area saw a 91% surge and Indianapolis jumped 76%, the AirDNA research shows.

Longer Stays

Many hosts concerned about the risk of penalties or legal costs are turning away from short-term vacationers to focus on month-to-month rentals. Longer-term stays can be far less profitable but aren’t as widely regulated.

“People can’t deal with the fines,” said Kazmin Thibault, an Airbnb host for more than a decade in Burlington, Vermont, which last year approved tighter short-term rental rules that include city permits and a 9% tax.

Thibault got her start in 2012 by renting her apartment to make extra cash on weekends, when she could stay with her parents. Now, she’s shifted away from vacationers to focus on longer stays.

Thibault said her monthly income has been cut in half, from about $6,000 with mostly short-term stays to about $3,100 for stays lasting three to six months. Anything longer, she averages about $2,000 a month, she said.

Read More: Short-Term Rentals That Airbnb Turned Into a Rage Are Struggling

Medium-Term Demand

Airbnb says active listings of all durations around the world jumped 19% in the second quarter from a year earlier to more than 7 million, adding more net active listings than in any quarter in the company’s history.

While short-term stays still make up the majority of Airbnb bookings, demand has surged for medium-term bookings lasting more than a month but less than a year, the company said in a note.

In the fourth quarter of 2022, stays of 28 nights or more were Airbnb’s fastest growing category by trip length and accounted for 22% of gross nights booked, up from 16% in the fourth quarter of 2019, according to Airbnb.

Month-to-month rentals aren’t new, but they’ve traditionally been at the lower end of the market with low-quality housing targeted at people with uncertain employment or low incomes, said Edward Coulson, director of research at the University of California Irvine Center for Real Estate. That’s changing.

“Transitioning into the medium-stay market means that you’re gonna have units all across the quality spectrum that are available for month-to-month leases,” Coulson said.

To be sure, longer stays also bring the risk of local eviction laws being applied to property owners that previously didn’t have to worry about them. In New York and Kansas, anyone who stays longer than 30 days is considered a tenant rather than a guest.

--With assistance from Natalie Lung.