Achim Wiechert was one of the many experts brought in to mend the broken market for bank capital securities in the aftermath of the financial crisis. He worries it could break again — and he’s on a mission to fix it.

The head of external funding at insurance giant Allianz SE is lobbying for one of the most far-reaching overhauls to Europe’s $235 billion market for additional tier 1 bank debt since it was created more than a decade ago to prevent a rerun of 2008’s taxpayer-led bailouts.

He’s held discussions with policymakers at the European Central Bank, the European Banking Authority and the European Commission to present his proposal. And now he’s talking publicly for the first time about his plan.

Wiechert’s concern is that AT1s, which count as capital, will fail to buffer banks from another crisis. This isn’t a flaw of the bonds themselves but of market behavior: Convention dictates that banks repay the notes at their first call date, whether or not it makes economic sense.

And at a time when they really need the capital, in a crisis, lenders would be even more compelled to follow those conventions, swallowing punitive debt costs so they can show it’s business as usual. He argues that the need to keep up appearances could plunge banks into trouble.

“I’m getting frustrated, in a way, that we see exactly the same thing happening,” Wiechert said in an interview. “The idea was to make AT1s truly perpetual so that we wouldn’t experience one of the worst things in the financial crisis, which was banks calling Tier 1 instruments and seeing them replaced with state aid.”

His solution is to take the decision on whether to repay AT1s early out of banks’ hands, and leave it up to market math. Either a replacement bond can be cheaper than a predetermined level or the bank will be barred automatically from exercising the call option.

A rule on calls could also mark a fundamental shift in the way investors and traders treat and price in those call options, making decisions more predictable and preventing sharp price moves around the announcements.

In the aftermath of the financial crisis, Wiechert took part in consultations around the rules that became Basel III and set the stage for the development of AT1s. Since then, he’s helped make Allianz the most active issuer of Restricted Tier 1 notes, which arose from the European insurance industry’s own post-crisis rules on capital.

What drove Wiechert, in part, to take up his campaign for better AT1 practice were some of the decisions that led up to the wipe-out of $17 billion of Credit Suisse notes in its government-brokered takeover in March.

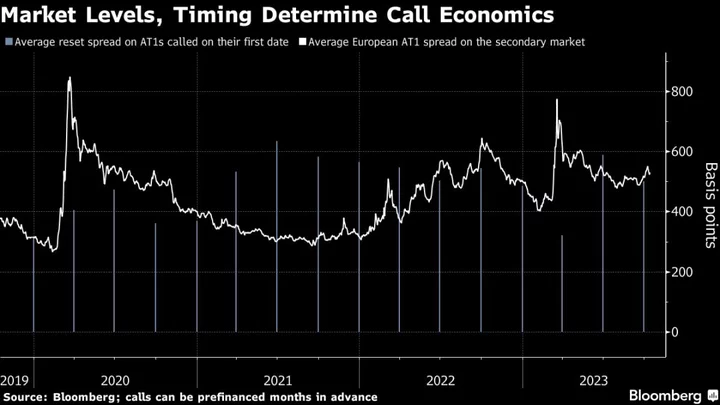

The Swiss watchdog signed off Credit Suisse’s last ever AT1 replacement in the summer of 2022, which added about 125 basis points to its annual costs. Crosstown rival UBS Group AG triggered a price jump in its AT1s later that same year when it announced an early redemption even though they would have been cheap to retain.

He took his grievances to the ECB, the EBA and the European Commission and presented his proposal to them over the past year. These discussions took place at working level, with early discussions being highly technical and focusing on the details.

Spokespeople at the ECB and the European Commission declined to comment. A spokeswoman at the EBA said the organization often engages in discussions with stakeholders on capital aspects and has no further information to share at this stage.

“As long as calls are viewed as individual decisions that can signal something beyond pure replacement economics, we have a problem,” said Wiechert. “We have set in motion a vicious circle of ever-more uneconomic calls.”

It’s an issue he faces himself in his current role at Allianz. More than once he’s been dogged by questions from investors about whether Allianz would call a Restricted Tier 1 note it sold in the past.

There are already guidelines in place on how to deal with uneconomic replacements. And regulators can already block a replacement if it’s too expensive. In practice, they have allowed several uneconomic decisions, including when a jump in interest rates and spreads since early 2022 turbocharged the cost of issuing new capital.

Even before AT1s arrived on the scene, banks, regulators and investors were at cross purposes over how to treat securities that may never mature.

Banks using perpetual notes for capital purposes — and the regulators approving them — wanted a degree of permanence, and fixed income investors wanted to get their money back at a predictable time. To square the gap, banks started including step-up coupons on some of their securities. That meant if they didn’t repay the notes at their first call date, the interest rate would eventually ratchet up.

When the financial crisis toppled one bank after another, investors in capital securities were made whole as taxpayers bore the brunt of the cost of bailouts.

Afterwards, regulators trying to right those wrongs came up with new definitions on core capital and bankers developed securities that fit those criteria. These perpetual securities don’t incur penalties if issuers decide not to repay them at the first possible opportunity — and if a bank gets into trouble they can skip coupons altogether.

AT1s, also called contingent convertible, or CoCos, were born, and grew into a risky and high-yielding market worth hundreds of billions. Lenders in the US issue preferred shares for this purpose and purely economic calls are a generally accepted practice there.

Call Them AT1s or CoCos, Here’s Why They Can Blow Up: QuickTake

The trouble is, investors outside the US still expect to get repaid when AT1s become callable — no matter the cost to the bank.

There was an outcry when Banco Santander SA let a call date on its AT1s lapse in 2019. During the pandemic years, a few other banks left their AT1s outstanding when primary markets ground to a halt and left them with few ways to refinance. By and large they kept calling them; even in 2020, 86% of the issues were called at the first opportunity.

Right now, European banks are well-capitalized and calling their AT1 notes early isn’t damaging them. But Wiechert warns these early calls are setting a dangerous precedent and could make the capital useless for when they really need it one day — just like in 2008.

“Issuers do exactly the same thing. Supervisors do exactly the same thing,” Wiechert said. “It’s time to stop that.”