The German government’s struggle to hammer out a revised budget after a shock court ruling last week not only gave a boost to the opposition but also stoked fresh infighting within the ruling coalition.

The constitutional court decision provoked already gaping policy differences between the three coalition parties – Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s center-left Social Democrats, Finance Minister Christian Lindner’s pro-business Liberal Democrats and the Green Party. But now those differences are threatening the alliance’s ability to govern and have spurred talk that the coalition may fall apart.

Scholz and his close confidants are locked up in near non-stop negotiations behind closed doors to try and solve the budget crisis. The stakes couldn’t be higher for Scholz as the outcome of the talks will essentially define the remaining second half of his legislative term and determine if he stands any chance at all of staying in power beyond 2025 when the next federal election is scheduled.

The mood was accordingly grim when Economy Minister Robert Habeck appeared at a Green Party conference in Karlsruhe on Thursday. Many of the more than 800 delegates were frustrated about the painful cutbacks that the Greens are now facing as a result of the ruling.

“We have become hostages of the FDP,” Klemens Griesehop, a delegate from Bremen, said about his Liberal Democrat partners, and referred to their policies as a “neo-liberal agenda.”

“How do we want to continue to govern with such a party without betraying our own ideals?” he said.

The budget dilemma will force Habeck to scale back his ambitious climate agenda. But he managed to calm the widespread frustration in the room with an emotional speech that called for a Green offensive within the government.

He launched an attack against the so-called debt brake, a constitutional limit on net new borrowing, which is a pet project of the governing Liberals, but also of the conservative opposition.

“With the debt brake we have voluntarily tied our hands behind our backs and are going into a boxing match,” Habeck told the delegates. “Is this how we want to win? The others are wrapping horseshoes in their gloves — we don’t even have our arms free.”

He also criticized conservative opposition leader Friedrich Merz who repeatedly met with Scholz in the past few weeks in order to sound out the possibility of a bipartisan agreement on a more restrictive migration policy. Many Greens fear that this could pave the way for another grand coalition, an alliance between the Social Democrats and the CDU-led conservative bloc, which would send the Greens back into opposition.

The CDU, Habeck said, “is a party from yesterday with a leader from the day before yesterday.”

He lashed out at the very same coalition that, under the leadership of former Chancellor Angela Merkel, had brought Germany into this mess in the first place “with its blindness toward Putin, toward China and toward the climate crisis.”

Habeck’s emotional speech may have averted a revolt among the base of the Green Party that has been pushing to ditch Scholz’s coalition. But even Habeck’s performance cannot undo the fact that support among voters for Scholz’s government has fallen to an all-time low.

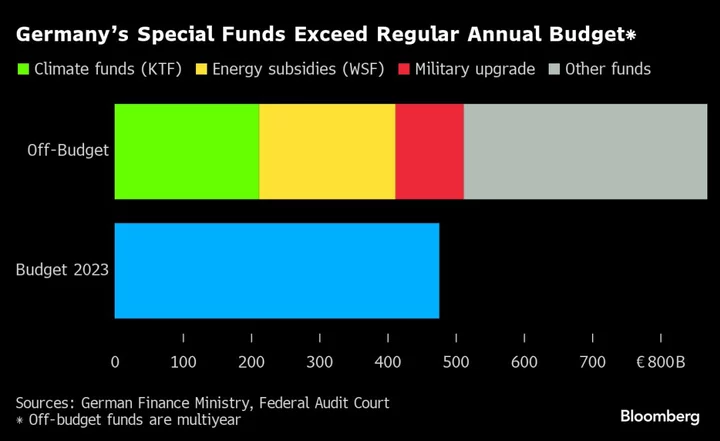

This had already been the case ahead of the decision by Germany’s top court that shot down the government’s excessive use of huge off-budget funds to help finance a fundamental overhaul of the industrial backbone of Europe’s largest economy.

According to public broadcaster ZDF, support for Scholz’s SPD is at 15%, the Greens at 15% and the Liberals at 5%. About 82% of Germans believe that relations between the three governing parties is bad.

But what must be even more worrying for SPD and Greens, who want to loosen the debt brake, is that 61% want to keep it as it is, and only 35% would agree to higher debt.

The Greens are arguably hit hardest by the recent turn in events. The party that traces its roots back to pacifist and environmental movements in Germany 40 years ago was first confronted with the dramatic reality of Russia’s war against Ukraine and is failing to deliver on its ambitious climate goals. Germany was forced to revive and extend coal power to avoid energy bottlenecks after the Greens and SPD leaders insisted on phasing out the country’s nuclear power plants.

The liberal Free Democrats are also facing an internal litmus test. More than 500 of its members have spoken out in favor of a party survey on whether to remain in the coalition. The party’s statutes state that once this number of signatures is reached, all of the roughly 75,000 members must be asked about the issue in question.

However, the official request has not yet been submitted by the party headquarters, according to the the party’s spokeswoman. Moreover, there is a counter-initiative within the FDP on its way to stay in government. The party is fighting for survival and is concerned about history repeating itself: Exactly 10 years ago, the FDP lost its parliamentary representation after having been in government. Lindner took over afterward.

The FDP members’ initiative shows a rift in the party that was previously unseen, Lindner had the party firmly under control since he’s in charge. “What irritates me somewhat is that even very level-headed FDP politicians, such as the former Bavarian Science Minister, are taking part,” said Ursula Muench, director of the Academy for Political Education in Tutzing.

Non-Stop Talks

Compared to the infighting among the Greens and the FDP, the SPD has sought to paint a unified front. No party official is openly questioning the leadership of Scholz, who belongs to the more pragmatic and business-friendly part of the center-left party.

In a video statement published Friday, Scholz promised that financial aid to ease the burden from high energy prices was not under threat and that the government won’t be diverted from initiatives including maintaining support for Kyiv and modernizing and greening Europe’s biggest economy. “We will continue to follow all of these goals,” he said.

Still, members of the SPD’s left-leaning wing such as party co-leader Saskia Esken and its general secretary Kevin Kuehnert have raised the pressure over the past days by categorically ruling out cuts on social welfare spending and calling for a suspension of the debt brake for both this year and next to safeguard planned investments for climate protection and industrial transformation.

It’s not just a few ‘hotheads’ who want to break up the coalition,” said the Academy for Political Education’s Muench, adding, however, that “it’s not threatening at the moment but that could of course change.”

Author: Arne Delfs, Kamil Kowalcze and Michael Nienaber