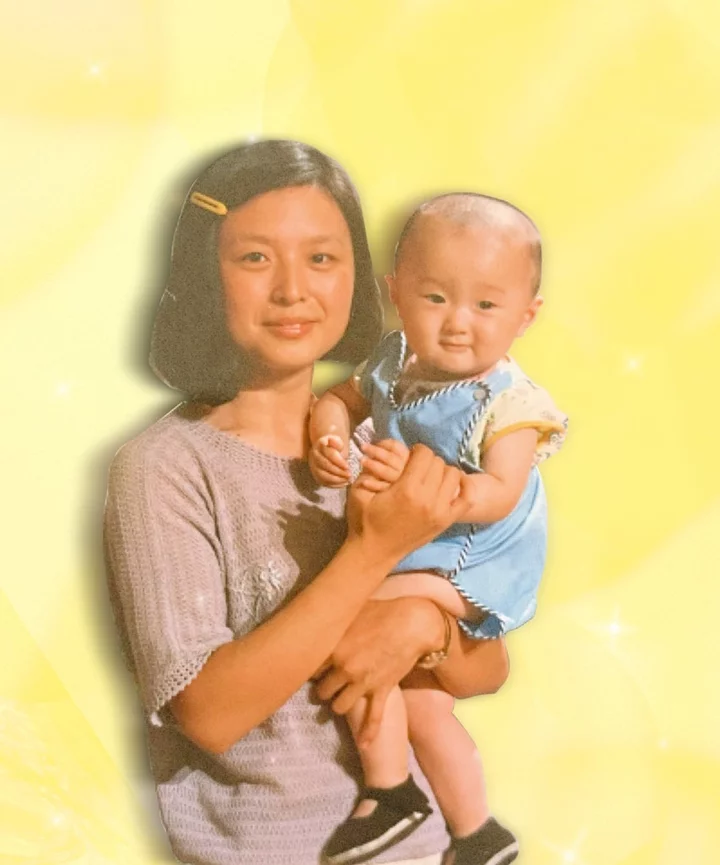

I began writing my memoir without knowing how it’d end — a strange thing to say about a type of book that’s literally comprised of the memories that already reside in your own head. But I had no idea what I was driving toward as I began typing out the pages that’d eventually become Oh My Mother!, a book about the relationship I had and have with my own mother, Qing Li, who came to the United States in 1988 on a trip to visit my father who was studying abroad, found herself stuck in a new country and unable to return home, and was forced to begin the taxing process of reinventing her whole life at the age of 28.

All I knew was that the book would have to be written in collaboration with my mother, which is a daunting enough task for any daughter whose mother is the one person in the world who should understand her best — and conversely, every mother hopes that her daughter grows up to understand her in a way that no one else can. But for my relationship with Qing, that expectation was especially challenging. Having learned English from textbooks, Qing can read and write English far better than I can, but speaking-wise, she’s as bad at English as I’m bad at Chinese. During good conversations, we both self-censure and modulate to each other’s comprehension, speaking in carefully honed Chinglish that relies on the more elementary vocabulary of our own stronger language.

One of my earliest memories — the kind you force yourself to remember because the experience is so disorienting that you feel yourself growing up while it’s happening — was a talking-to. The circumstances in which I had gotten in trouble are lost on me now, but Qing was attempting to explain the concept of being considerate. It was important that I know what this word meant, she said solemnly, in a voice that made me feel like I also needed to be as mature as possible.

“Do you know the word for respect in English?” she asked in Mandarin. “You need to be more respectful. Do you know the word for respect?”

I nodded my head. I was pretty sure I knew. On TV, there was only one word people had to whisper when they said it, and they only said it around grownups, with the same searching, grave countenance of my mother’s.

“Sexy,” my four-year-old self said. “I need to be sexy.”

Neither of us said anything further as we both realized we had missed by miles, and that miles was the best either of us could hope for.

The lack of expression must have driven her crazy. In China, she was a big-shot editor at a publishing firm who loved words and lived in them. But her story in America started with a misunderstanding about what translates between Chinese and English, and China and America, and more crucially, what doesn’t; my father didn’t realize that participating in student protests would be noticed, and thus her year-long vacation visiting him as he completed his graduate degree abroad would become a permanent move. The first decade or so of her time in America was spent agonizing over what else she may have misunderstood, and what disaster was awaiting us.

And so, during bad conversations, our communication completely fell apart. As a kid, expressing myself in the most elementary of ways — to my mother, about something that had happened, about something I was feeling — was inordinately difficult, nearly impossible, and unwelcome. Her anger at my lack of prudence, or thoughtfulness, or neurosis, used to come on like a fog, quiet and blinding. But we had long ago moved past this phase in our relationship, as she began to trust that I wasn’t the kind of person who’d let unforeseen circumstances upend her life like she had, and I understood that the rage she expressed was just fear in disguise.

But, even so, I had committed myself to writing a book that would have to be based on long discussions with my mother, about something that happened, about something we had felt and did feel. I did not know how the book would end, because I did not know if this was possible. All I knew was that the conversations we could have had has never haunted me, though people who inquire about the awkwardness with which my mother and I communicate convey that it must weigh on me, with compassion in their eyes. But how can I miss something that I never had?

And so we began talking, mostly standing in the kitchen with our backs resting against adjacent countertops as we bounced and fed and rocked my newish-born son. It struck me that I was writing about Qing about a time when she would have been younger than I was, and it made me feel both very old and very naive. And so we began there: There was so much I did not know about parenthood, and I was curious. We talked about what it was like for Qing to become a mom, of finding out her birth control had failed. Of how that felt so similar to when she realized she couldn’t return home, and that she was stuck in a country that she barely liked, and definitely didn’t understand. Of what it was like to have to give up a career she loved and was good at — and eventually seeing her daughter embark on the same path.

These conversations were excruciating, embarrassing, and confusing. Many of them ended in tears, and not the heartwarming kind. They took twice as long as they could have, not only because we could only use half of our vocabulary, but also because, this time, we didn’t skip over what wasn’t clear. We practiced expressing ourselves, and when we couldn’t, we allowed each other to try and tell it back in different ways until we got it right. We engaged in this because it was an assignment, but we applied ourselves because of what it felt like when we finally understood what the other one meant.

I can now tell you this: Being understood, the way I see it, is not the way it’s often depicted in movies, like being instantly struck by love, or magicked into existence from some ancient, metaphysical soulmate bond. Nor is it a blessed shortcut from ever having to explain yourself. At least not for me. Being understood is always getting to explain yourself. The way I’ve come to be understood has always grown from complication and friction, from attending to another and giving them room to talk — and knowing that you’re being offered the same. Qing and I still barely understand each other on a sentence-to-sentence level, but together, we’re getting quite good at being understood.

Two years later, and the book is finally out. When people find out that I wrote a book about my mother, the No. 1 question they ask, in the same tone people use to mine for gossip, is whether my mom has read it yet and what she thinks. I understand why people ask it — so many stories about families, especially families who’ve lived through difficult things that end up in books, are told because one person has found the courage to tell the truth. But my truth is that my bravery lies in not doing it by myself, for once. I can say that I worked as hard on understanding her truth as I worked to put mine down on paper. And though there is a last chapter, I know that I am nowhere near finishing what we had started.

Connie Wang is a writer, journalist, and former executive editor of Refinery29. Excerpts of this essay appear in OH MY MOTHER! by Connie Wang, published by Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2023 by Super Rare Inc.