Investors face a new era of supply-chain risks with the potential to hit asset values, as the US expands enforcement of a law targeting forced labor in China’s Xinjiang region, according to JPMorgan Chase & Co.’s head of ESG equity research for the Asia-Pacific region.

Hannah Lee, who oversees environmental, social and governance research for JPMorgan from Hong Kong, says she and her team have been closely monitoring how the US Customs and Border Protection agency is implementing the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act, which came into force in June 2022.

With the agency including the auto-parts industry in its scope earlier this year, “we noticed that CBP has got additional resources under its belt and is ramping up in terms of recruitment and the general resources available to it,” Lee said in an interview. “We do expect increasing scrutiny on new areas and more sophisticated supply chains than we’d seen before.”

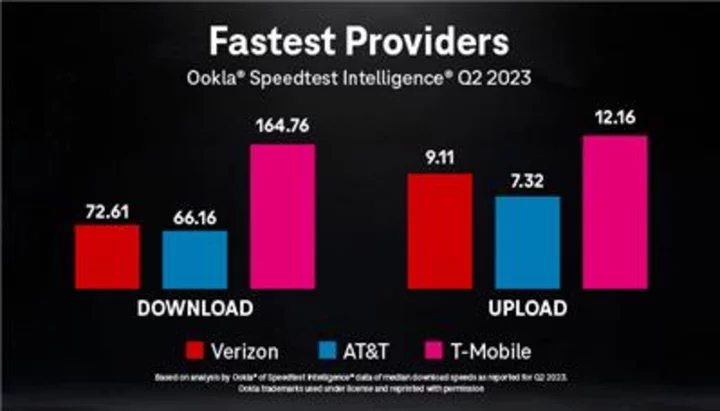

It’s the latest sign that no matter how much political backlash engulfs “ESG” as a label, ignoring what it stands for is riskier than ever. Recent examples include AT&T Inc., which has lost about 8% of its market value since early July, amid reports its cables contained toxic lead. And companies that fail to monitor their supply chains are increasingly likely to be called out, thanks to services such as the Human Rights Foundation’s Uyghur Forced Labor Checker.

Read More: NY Pension Fund Presses AT&T, Verizon Over Toxic Lead Cables

Congress passed the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act unanimously in 2021 with support from labor unions and activists. It seeks to put pressure on Beijing for allegedly detaining minorities in Xinjiang, an autonomous region in northwestern China that’s home to millions of Uyghurs.

The measure bars the import of goods that were manufactured using forced labor in China, especially from the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region.

Read More: China Forced Labor Law Prompts Sweeping Supply Chain Reviews

“We do feel like there is an increasing financial materiality for social-related risks,” Lee said. “In the case of UFLPA for example, you’re actually implementing an issue around human rights through trade laws. So that limits market access, which of course can be financially material.”

Another metric JPMorgan is monitoring is the extent to which stocks are held by ESG investors, the idea being that a high ratio of ESG ownership makes a company more exposed to investor exclusions if supply-chain controls are found to be lacking.

Such assets “are more likely to potentially have sell-downs triggered by some of these controversies,” Lee said.

It’s a risk that’s also been identified by analysts at Societe Generale SA, who noted that such selloffs look set to become more common with ESG investors projected to hold roughly a third of the total global asset market by 2025.

Lee says investors would be wise to pay attention to the sectors that the CBP is adding to its list. The office has so far focused on electronics and apparel, where there’s been the biggest enforcement, she said.

“We would expect increasing focus on these new categories,” she said. The expanding scope “suggests an increased level of ambition by CBP to enforce UFLPA in an increasing number of supply chains, including more sophisticated supply chains like autos and auto parts.”

There is “increasing focus on the ‘S’ within ESG,” Lee said. “And supply chains are coming under more scrutiny.”

--With assistance from Gina Turner.