Latin America’s top central bankers reinforced their inflation warnings at a high-profile event in Sao Paulo on Friday, standing firm against growing pressure for interest rate cuts.

Political leaders, investors and businesses across the region that led the world into an aggressive monetary tightening campaign after the Covid-19 pandemic are now anticipating — and in some cases demanding — imminent rate reductions as inflation slows from multi-year highs.

Yet Colombia’s central bank President Leonardo Villar said he still can’t rule out an extension to the country’s most aggressive tightening cycle ever, while his Chilean counterpart Rosanna Costa said core inflation rates are high. Peru’s Julio Velarde warned that political pressure for rate cuts “will remain” but that policymakers should not give in.

“Central bankers are more cautious after such a long period of above-target inflation,” Cassiana Fernandez, a Latin America economist at JPMorgan & Chase Co, said ahead of the meeting.

Justified

For policymakers like Brazil central bank chief Roberto Campos Neto, the Sao Paulo gathering was a chance to rally together to make the case to impatient politicians that their caution is justified.

Campos Neto, who hosted the event, has faced unrelenting criticism from President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva and Finance Minister Fernando Haddad over the decision to hold Brazil’s key rate at a six-year high of 13.75%, even as annual inflation has fallen more than 8 percentage points from a year ago.

“We need to understand that discussing monetary policy isn’t an affront to the central bank,” Haddad said at the opening of the event. He later told journalists: “We understand a window is opening for a cycle or rate cuts.”

Others may soon find themselves in similar scenarios. Chile’s annual inflation rate is in single digits for the first time in 13 months. Even Colombia, a regional laggard that saw prices accelerate at their fastest pace since 1999, has finally reached its “turning point,” Villar told Bloomberg News ahead of the event.

Read More: Colombia’s Inflation Hit ‘Turning Point’ in April, Villar Says

Traders in Chile, Brazil and Colombia now price in odds of rate cuts starting in the second half of 2023. Investors in Mexico, where policymakers this week paused hikes, expect easing to begin before the end of year.

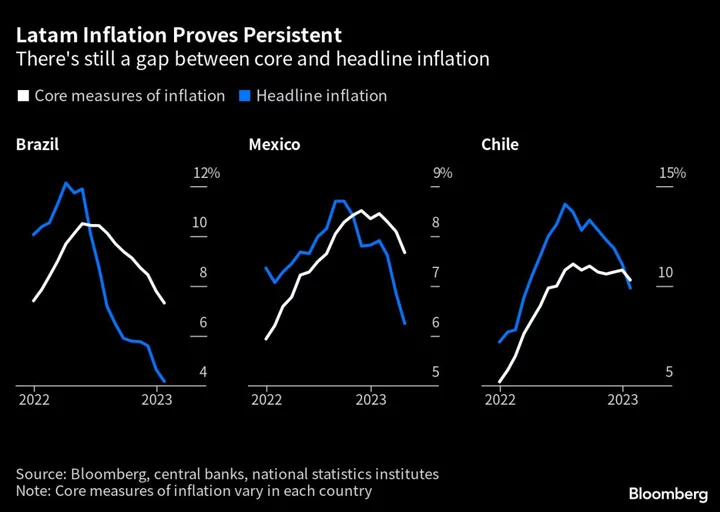

But dogged by fresh memories of forecasting failures during the pandemic, central bankers across the Americas have pointed to worrying signs in underlying price gauges.

Headline inflation may be tumbling in response to lower commodity prices, falling food costs and regional currency appreciation. But the picture isn’t as rosy as it seems when volatile items like food and energy are excluded, and inflation isn’t likely to hit central bank targets across the region until late 2024.

Labor markets, meanwhile, are holding up against restrictive monetary conditions and tepid growth, with unemployment rates at pre-pandemic levels. Stronger services and measures of overall activity have also puzzled analysts who bet on more sluggish economic results.

Worst Outcome

Those factors have left Latin American central bankers on high alert. In Brazil, Campos Neto has warned that his country’s economy may be entering a new phase marked by painfully slow declines in core inflation and unhinged consumer price forecasts.

Brazil’s headline inflation prints are approaching 4%, but three months of tax cut-driven price drops at the end of 2022 make them appear lower than they should, analysts like Gustavo Arruda, a Latin America economist at BNP Paribas, say.

Chile’s Costa has cautioned leftover cash may still be slushing around its economy, after citizens made $50 billion in early pension withdrawals while government transfers reached 90% of households during the pandemic.

But the biggest fear plaguing central bankers in Latin America is even simpler: That their rate cuts will prove premature, forcing them to reverse course and start tightening again.

First Cuts

Investors still say monetary easing is not a matter of “if” but “when,” as the delayed effects of aggressive rate hikes in 2021 and 2022 hit local economies and growth falters.

Two of Latin America’s oft-overlooked economies — Uruguay and Costa Rica — have already embarked on rate cuts. A combination of falling inflation expectations and restrictive fiscal policies are likely to make either Peru or Chile the next in line around the middle of this year.

In Brazil, central bankers are monitoring the advance of legislation aimed at controlling debt and shoring up public spending, which could lead to rate cuts in September. Mexico and Colombia are likely to follow only later.

“Given how quick they were to raise interest rates, they will probably be among the first to cut interest rates, too,” Kimberley Sperrfechter, a Latin America Economist at Capital Economics, said about the region’s central banks.

--With assistance from Davison Santana.

(Recasts story, adds comments from event participants starting in fourth paragraph)