After almost a year of treading carefully, Italian Premier Giorgia Meloni is unleashing her brand of hands-on capitalism with greater gusto, and that’s making some investors nervous.

Bolstered by strong public support and stable borrowing costs, the 46-year-old prime minister is veering from earlier promises to follow the mainstream approach of predecessor Mario Draghi. In recent months, the right-wing leader has made a series of interventionist moves from airline fares to phone networks — and most notably a controversial late-night announcement to tax bank profits.

Since the June death of former premier Silvio Berlusconi — founder of coalition member Forza Italia — capitalist-friendly voices have been sidelined and the government has become more of a double act between Meloni, president of the Brothers of Italy, and Matteo Salvini, the populist firebrand who leads the League party.

The shock move to levy a 40% tax on bank profits, for example, was approved by her cabinet in August without consulting Forza Italia leader Antonio Tajani. The risk is greater volatility for Europe’s third-biggest economy.

“The tax on banks’ extra profits was a big mistake that heavily damaged our country’s credibility just to gather a small amount of funds,” said Veronica De Romanis, a professor of European economics at Stanford University in Florence. “The government says it’s taxing the excess, but who defines that? How do you explain that to investors?”

As Italy’s economy falters, Meloni faces a difficult test to show that she can continue to carry out her agenda. A surprise contraction in second-quarter gross domestic product makes it harder for Italy’s first female premier to find the funds needed to pay for promises to voters, keep her coalition in line and soothe wary bond markets.

Meloni, who has kept a low profile since the bank-tax announcement, passed up a chance to explain her strategy by skipping an annual symposium with investors and executives this weekend in Cernobbio on Lake Como. Deputies Salvini and Tajani will instead represent the government.

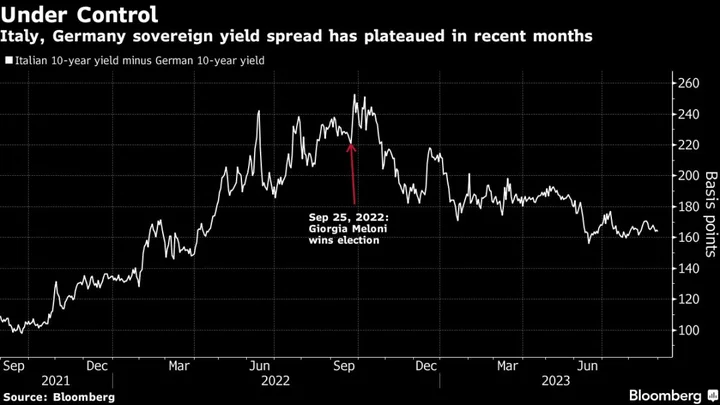

The coalition has so far stuck to fiscal prudence, keeping spreads between Italian one-year bills and German counterparts well below 200 basis points. A younger Meloni witnessed Berlusconi’s downfall in 2011 when a spike in bond spreads led to a collapse of the government. It’s a lesson she hasn’t forgotten.

“Meloni is acting in a pragmatic way, trying to find a balance where you’re not poking the markets in the eye too much,” said Giovanni Orsina, director of the School of Government at Rome’s Luiss University.

With public revenue uncertain, her administration is likely to slightly widen the deficit to pay for measures like tax cuts on wages, but will be careful not to go too far, according to people familiar with the matter, who asked not to be identified because the talks are private.

Her Brothers of Italy party has maintained a commanding lead in voter polls, with support stable at around 29% — well ahead of the combined backing for League and Forza Italia. As long as she maintains approval ratings and keeps financing costs in check, she has leeway to take a more activist role in Italy’s corporate affairs and she’s been taking the opportunity.

Aside from the bank tax, her cabinet passed a measure clamping down on airlines use of algorithms to set ticket prices — particularly for internal connections to the islands of Sicily and Sardinia. The move was aimed at protecting consumers against sudden spikes and caused a backlash from airlines.

Then there’s phone carrier Telecom Italia SpA. Italy approved a decree on Monday that empowers the state to take a stake of as much as 20% in its network business as part of an agreement with US private equity firm KKR & Co. for joint control of the country’s grid.

“Now Prime Minister Meloni has been smart enough and operational enough to put herself and the government immediately on the line of international markets and our allies in the EU and the US,” former Prime Minister Mario Monti told Francine Lacqua on Bloomberg Television. “Now is the time of financial law, the budget for next year.”

To help pay for some of her initiatives, Meloni’s coalition is considering selling minority stakes in selected state-owned companies, including state railway Ferrovie dello Stato SpA and long-troubled Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena SpA, Bloomberg reported this week.

The signal is that Italy is open for business but Meloni’s office is the gatekeeper. The approach is in line with her right-wing tradition, which sees the government taking a strong role in controlling the economy.

Another example is a measure passed in August, which calls for a special commissioner to be assigned to foreign investments of more than €1 billion ($1.1 billion).

Meloni’s government also has given itself the authority to block technology transfers to countries outside the European Union in strategic sectors such as artificial intelligence, semiconductors, aerospace and energy. The law even applies to sharing intellectual property between corporate entities.

Timing has also been on Meloni’s side. She took power as the terms were expiring for several state company chiefs and other key officials. This allowed her to swap out some of the top players in Italian capitalism including the head of energy giant Enel SpA and nominate the new Bank of Italy governor, who sits on the European Central Bank’s Governing Council.

“There is a return of the state,” said Orsina from Luiss University. “Italians vote Meloni because they crave security and the nation state as an element potentially able to guarantee that security.”

--With assistance from Chiara Albanese, Sonia Sirletti, Giulia Morpurgo, Giovanni Salzano and Antonio Vanuzzo.

(Updates with Mario Monti comment in the 14th paragraph.)

Author: Alessandra Migliaccio, Flavia Rotondi and Alberto Brambilla