Some of the world’s biggest corporate consumers of air travel are investing in cleaner jet fuel, using a new credit system aimed at allowing the companies to claim the environmental benefits.

Microsoft Corp. has made one of the largest commitments. The tech giant has long pledged to become carbon negative by the end of this decade, meaning it plans to remove more climate pollution from the atmosphere than it emits.

To tackle the heat-trapping emissions from its journeys, Microsoft has reached two recent deals: In August, it agreed to work with British Airways owner IAG SA and Phillips 66 to co-fund the purchase of nearly 5 million gallons of sustainable aviation fuel, made from sources like used cooking oil and food waste. It hatched a subsequent deal with clean-fuels producer World Energy LLC to purchase credits for nearly 44 million gallons of SAF over the next decade.

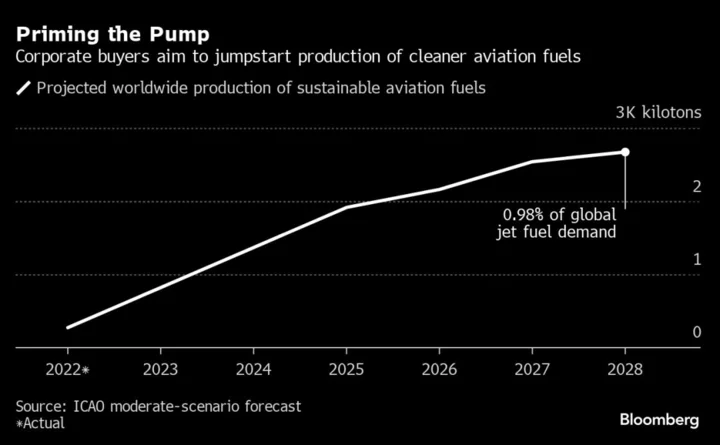

Globally, SAF now accounts for about 0.1% of all aviation propellant. The expected 4.4 million gallons a year from the World Energy deal could propel Microsoft ahead of most major US airlines. It’s equal to the combined SAF usage last year by American Airlines Group Inc., Delta Air Lines Inc. and Alaska Air Group Inc. The US leader, United Airlines Holdings Inc., consumed 2.9 million gallons of SAF in 2022, and has targeted 10 million gallons this year.

“Hopefully our early adoption creates a more robust market where we will see higher adoption across the board,” said Katie Ross, director of Microsoft’s carbon reduction strategy.

Google has similarly joined a program led by American Express Global Business Travel and Shell Plc’s aviation unit, while this month, European delivery giant DHL Group agreed to buy credits for about 180 million gallons of SAF over seven years.

Now some two dozen companies including Morgan Stanley and McKinsey & Co. are close to finalizing transactions totaling a combined 100 million gallons of cleaner jet fuel over five years, through a group called the Sustainable Aviation Buyers Alliance.

In each case, the companies aren’t acquiring the liquid jet fuel itself. Rather, they’re buying certificates that allow them to take credit for the lower carbon-emission profile of fuel that is combusted elsewhere. The credits are also meant to encourage production of SAF by providing an extra revenue stream, while expanding the pool of buyers.

“These companies are helping to kick-start this market and get it moving, showing that there is end-consumer demand,” said Andrew Chen, a principal at the Rocky Mountain Institute, an environmental nonprofit that helps run SABA.

The efforts are intended to crack a problem that has long vexed the climate community. Aviation contributes about 2.5% of manmade CO2 emissions and has caused 4% of warming when including the impact of things like contrails. Its share of carbon-dioxide pollution could soar well past 20% by 2050 with the expected growth in air travel and the decarbonization of other parts of the economy through electric cars and renewable energy.

SAF costs more than twice as much to produce as conventional jet fuel. It’s made at only a handful of facilities around the world. Most commercial airlines have pledged to dramatically increase their SAF use to 10% of fuel by 2030, but progress has been ponderously slow.

The new certificates are designed to spur the market by covering the cost premium of cleaner fuel, while giving the buyers a way to potentially lower their own greenhouse gas emissions. They split cleaner jet fuel into two products: the liquid itself, which can be sold in traditional ways, and the SAF certificate, which represents the environmental benefits associated with cleaner fuel.

Other financial instruments targeting climate changed have been tripped up by credibility issues. The multi-billion dollar market for carbon offsets has produced low-quality junk that dragged down demand. Renewable energy credits, structured in a similar way to SAF certificates, have sometimes led to bogus carbon accounting.

It’s too soon to tell if the new programs for SAF credits will avoid these pitfalls, but there are early reasons to be optimistic. For starters, price for the SAF certificates is hefty – from $250 to $800 for every metric ton of carbon dioxide avoided. That’s a hulking price compared to carbon offsets and renewable energy credits — whose cost, at less than $10 per ton, helped to enable abuse.

SAF proponents also maintain that this market is fundamentally different because there’s a real shortage of sustainable jet fuel, unlike when renewable electricity credits came into use.

“There’s a lot more value in this type of investment,” said Chen, of the Rocky Mountain Institute.

Still, it’s unclear whether enough companies will step forward to have an impact on production. It can cost about a half-billion dollars to build a clean jet-fuel plant. “We’re watching the market form,” said Bruce Fleming, chief executive officer of Montana Renewables, one of two commercial SAF producers in the US. “That’s going to take a while.”

A booming market for SAF certificates could help spur a stronger recovery in corporate travel, which has yet to bounce back completely since the Covid-19 pandemic. Some businesses have drastically lowered business flights to address climate concerns.

Environmental groups, however, point out that any jump in corporate travel would be tragic for the climate. European nonprofit Transport & Environment has called on businesses to halve their air-travel emissions by 2025. “SAF should not be an excuse to fly more,” said T&E policy officer Camille Mutrelle. “We have to be very clear about that.”

Although rules for the market are still being formed, the certificates should only apply to SAF that isn’t already being used to comply with legal mandates, such as European Union rules requiring airlines to use 2% sustainable fuels by 2025. Once issued, the certificates can be tracked by one of a half-dozen nascent registries tasked with ensuring the same SAF isn’t claimed by multiple buyers.Selling the certificates separately opens the SAF market to new buyers beyond typical airlines. It also allows companies to participate if there are no tanker trucks full of SAF nearby.

“Moving low-carbon molecules all over the place in the interest of decarbonization just doesn’t make sense,” said Gene Gebolys, chief executive officer of World Energy, which is also producing the SAF that will be claimed by DHL.

Still, it’s not clear how companies will be able to take credit for their purchase of SAF certificates. GHG Protocol, the world’s most widely used carbon accounting standard, doesn’t currently allow companies to report lower travel emissions by using them. It’s weighing evidence about whether a change is warranted.

Allowing companies to use SAF certificates to lower their emissions tallies will be key to growing this market, according to Brian Ripsin, a sustainability manager for Shell Aviation. “That’s the next major hurdle we need to overcome to get more large-scale adoption.”