A popular category of carbon offsets held by a number of major publicly traded companies is significantly more prone to greenwashing than previously feared, according to a new investigation of the financial instruments.

The conclusion is based on work done by a team of 14 researchers in association with the University of California, Berkeley’s Goldman School of Public Policy. The study looked at so-called REDD+ credits, which represent roughly a quarter of carbon offsets issued globally.

“Many of the researchers have been studying carbon-offset quality for many years, and even we were surprised,” Barbara Haya, director at the Berkeley Carbon Trading Project and the lead researcher behind the report, said in an interview. “We found problems under every stone we turned.”

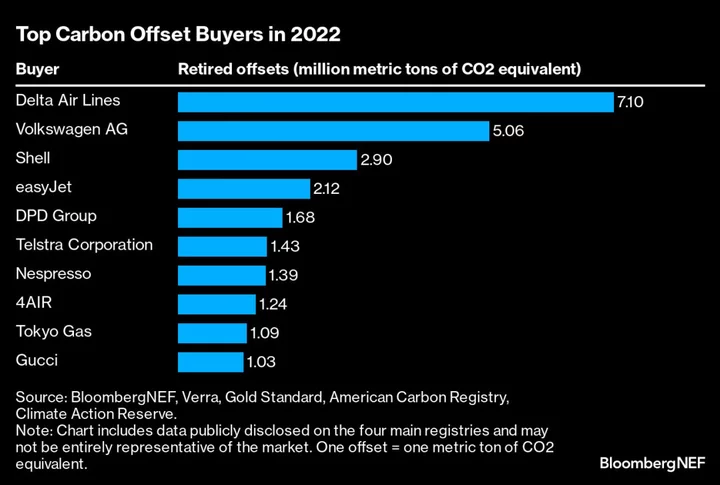

The findings may have serious implications for companies that have based their climate statements on the offsets probed in the study. That list includes Shell Plc, Eni SpA and Delta Air Lines Inc., according to an analysis of public data by Carbon Market Watch, a nonprofit that commissioned the Berkeley research.

The study also has ramifications for the traders of offsets, according to Gilles Dufrasne, global carbon markets lead at Carbon Market Watch.

Traders and companies that end up buying offsets need to “do some work to figure out which ones are worth something and which ones are worth nothing,” Dufrasne said. “Most credits probably don’t represent any climate benefit.”

Haya said REDD+ credits can’t be viewed as a reliable tool for offsetting, so brokers trading them would be better off viewing them as “a donation.”

Trafigura Group, the world’s largest trader of carbon-removal credits, has already suspended a consignment of REDD+ offsets as it awaits the result of a probe into a forestry project behind the units.

And Bloomberg has previously reported that more than 75 million carbon credits currently lie dormant on the accounts of Vitol SA, the world’s largest independent commodity trader. Dutch trader ACT Commodities Group BV and ACT Financial Solutions, which are both units of SMS Holding BV, wrote off about 1.5 million credits last year.

Shell Appeal

Shell has already been called out by regulators for its claims around offsetting. Last year, the oil major lost an appeal against a ruling by the Dutch advertising watchdog that an ad campaign promoting carbon credits was misleading.

A spokesperson for Shell, which recently shelved a plan to develop its own carbon offset projects at scale, said such instruments remain “an important additional means” to support its target of reaching net zero emissions by 2050. “But they don’t replace our efforts to avoid and reduce emissions,” the spokesperson said, adding that Shell has “robust due diligence processes.”

“While we recognize the system isn’t perfect, it is continually improving,” the Shell spokesperson said.

A spokesperson for Eni said carbon offsets are “one of the many tools in Eni’s decarbonization pathway.” The credits are subject to audits and due diligence, according to the highest control standards applied by the company, the spokesperson said.

Delta hasn’t responded to a request for comment.

Haya and her team of researchers looked at four methods designed by Verra, a nonprofit that developed the Verified Carbon Standard (VCS) Program, to generate carbon credits from projects that protect forests. These allow developers to pick a baseline of predicted carbon loss in the project area based on historical deforestation rates in the region, and then measure change against that. The difference between those two carbon values is packaged and sold in the form of credits, based on so-called avoided emissions.

The approach differs from other methods that tend to generate more reliable measurements, such as planting trees or removing carbon from the atmosphere using new technologies. Rather than measuring hypothetical avoided emissions, such models measure the extra CO2 that’s actually been absorbed, and package that into carbon-removal credits.

The REDD+ programs that were the focus of the Berkeley investigation — which exist within the unregulated voluntary carbon market — “are really complicated and there’s a lot of uncertainty,” said Haya.

Developers are exploiting the flexibility in the system to “make assumptions and choose methods that give them more credits rather than less,” she said. The whole structure is “leading to highly exaggerated carbon credits.”

In the absence of regulators, market standards are monitored by a handful of nonprofits that host their own registries. And if one body tightens its standards, a developer can just go to another. Meanwhile, independent scientific analysis of projects’ CO2 reduction claims generally lags behind the issuance of the corresponding carbon credits, leaving buyers in the $2 billion market exposed to significant losses.

The researchers also zeroed in on the auditors providing stamps of approval to such projects. Without singling out any firms, the study said that in one case, an auditor approved a zero fire-risk rating for a project, even after observing a fire first-hand while visiting a site. Another case referred to a project in which claims about carbon preserved in trees were based on an unrelated article on water nutrients.

“The verifiers aren’t doing their job,” Haya said.

A spokesperson for Verra said the nonprofit welcomes the outside scrutiny.

The vast majority of the researchers’ findings align with extensive and systematic work to update Verra’s carbon crediting program, a spokesperson for the nonprofit said.

The Berkeley findings are the latest to raise questions about the carbon offsets market. The plunge in prices that has ensued reflects “heightened concerns about project quality,” Morgan Stanley analysts wrote in a recent note.

Efforts to improve the integrity of the market, such as the new standard set by the Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market’s Core Carbon Principles as well as the United Nation’s new Article 6 market, will be a “material tipping point,” the Morgan Stanley analysts wrote. But that comes after a 90% selloff in futures, they said.

William McDonnell, chief operating officer of the ICVCM, said the council is about to start assessing the methodologies carbon-crediting programs use to certify categories of credits, such as REDD+.

Last month, a separate study published in the journal Science that analysed 18 REDD+ carbon offset projects found that just 6% of a potential 89 million credits were linked to additional carbon reductions.

Haya says severe shortcomings in the REDD+ program are hurting efforts to fight biodiversity loss as well as climate change.

“It’s undermining both goals at once and taking funds away from more effective measures,” she said. “We do not have time for false solutions.”