Australia’s outgoing central bank chief Philip Lowe proved to be a convenient scapegoat for public anger over surging living costs and rising interest rates, meaning Friday’s decision to jettison him was little surprise.

Lowe’s seven-year term has been punctuated by extreme turbulence, ranging from global disinflation to a worldwide pandemic and the biggest European conflict since World War II — which have made operating monetary policy even more challenging than usual. The governor drew on all his experience to make judgment calls to cope with the circumstances and they didn’t really come off.

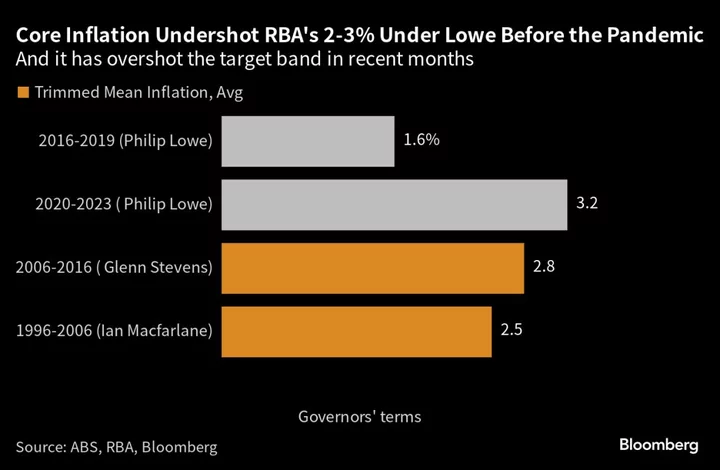

Initially, he held rates higher than economic circumstances would dictate before the pandemic and then, when Covid-19 hit, took the unprecedented step of telling Australians there was unlikely to be a rate rise before 2024. His aim both times was to do what he thought was best for the economy — with the latter guidance to provide confidence during a worldwide health crisis.

But Lowe, like other central bankers, was caught out by the breakout in inflation and had to tighten fast. As a result, the first hike came in May 2022, and people who took the respected RBA chief at his word were angry.

While most central bankers endure a backlash in tightening cycles, the aggression toward Lowe was unprecedented in Australia. Sky News and Sydney’s Daily Telegraph newspaper described him as a “dead man walking” and a TV camera crew was permanently camped outside the governor’s home.

“Phil Lowe’s position has been untenable for the past 6-12 months,” said Callam Pickering, chief economist at global job site Indeed Inc. “But his treatment over the past year — the unwarranted abuse for doing his job — has quite frankly been disgusting.”

Housing Bubble

A highly credentialed central banker who was well-respected by global counterparts, the quietly spoken and mild-mannered Lowe, 61, faced tough questions before the pandemic. At that time, grappling with disinflation, he refused to cut rates for an extended period to avoid a housing bubble.

It was a judgment call. He maintained the cost of borrowing wasn’t the problem and the economy needed more fiscal spending and business investment. In the end, as the economy stagnated, he resumed cutting after a three-year hiatus.

“The Reserve Bank needs help in prosecuting its management of economic cycles and help from fiscal policy makers and that hasn’t really been forthcoming over Governor Lowe’s term of office,” said Alex Joiner, chief economist at IFM Markets Ltd.

Later, in the pandemic, Lowe slashed rates to 0.1% and began unconventional monetary policy, which international experience has shown exposes central banks to political pressure and problems. Yet, determined to do all he could to support the economy, the RBA undertook quantitative easing and ran a yield-target policy, along with his 2024 rate-rise guidance.

Combined with a vast fiscal stimulus, the strategy proved successful and Australia became the first developed-world nation to regain the lost economic output as unemployment fell to the lowest level in half a century.

But Lowe allowed stimulus to drag on too long. The RBA began its tightening cycle in May 2022, later than the Federal Reserve and New Zealand, and moved more cautiously than many of its counterparts — Australia’s 4 percentage points of hikes compares with Fed’s 5 points and RBNZ’s 5.25 points.

The slow path reflected Lowe’s desire to preserve pandemic-era jobs gains and to engineer a soft landing in the economy.

“Anyone that knows what the Reserve Bank is supposed to do and what its charter says to do couldn’t really criticize Phil Lowe,” said Bernie Fraser, RBA governor from 1989-1996.

The 2024 forward guidance “had some unfortunate consequences. Much as you might want to respond to appeals for more information about what the bank’s going to do in future, you just can’t do that when there’s so many fundamental uncertainties out there.”

Lowe apologized to Australians for that guidance during parliamentary testimony earlier this year, saying he was “sorry if people listened to what we’d said and then acted on that.”

As recently as Wednesday Lowe expressed a desire to stay in the job, saying he’d be “honored” if asked to continue but if not, “I will do my best to support my successor.”

Also on Wednesday, he announced the RBA’s rate-setting board would begin implementing recommendations of an independent review of the RBA. It will move to eight meetings a year, from 11 now, in 2024 and there will be a press conference after each one.

Lowe will not be around in the new era. Instead, his deputy since April last year, Michele Bullock, will take the helm from Sept. 18. Lowe’s 43-year career at the RBA will thus end when the first woman to lead the bank takes charge.

“It’s a quality appointment,” Bill Evans, outgoing chief economist at Westpac Banking Corp. told Bloomberg TV Friday. “We’re in store for someone who’s courageous, someone who will be very well trained and going to provide the stability that’s needed to move the Reserve Bank to its next stage.”