Cirrus Aircraft Ltd. is proud of its history in the US heartland: the private plane maker’s website includes details such as the company’s 1984 launch in a Wisconsin barn, the opening of a Minnesota R&D center and a North Dakota factory.

But there’s something missing from the company’s All-American timeline: Cirrus’s ownership by a sanctioned Chinese military manufacturer.

For more than a decade, Cirrus has been a subsidiary of Aviation Industry Corp. of China, a maker of fighter jets, helicopters and drones for the People’s Liberation Army. AVIC, as the parent company is known, is also one of the world’s largest military contractors and is subject to US sanctions.

Cirrus isn’t a military manufacturer — its main products are single-engine planes used by private citizens and charter services — but some of its technology and manufacturing expertise could be valuable to the PLA, according to several aviation and Chinese military experts interviewed by Bloomberg. In June, the company filed with the Hong Kong stock exchange for an initial public offering. Its expansion, despite deep tensions between Beijing and Washington, underscores the complex political calculations underlying US sanctions.

“There’s an imperfect, Swiss-cheese approach to this,” said Sarah Kreps, a professor of government at Cornell University. Policymakers “haven’t pulled all the threads to ensure there aren’t these blind spots in the sanctions regime that’s in place.”

Cirrus hasn’t been accused of any wrongdoing and there’s no sign the US is seeking to target the company. But its parent company is under a great deal of scrutiny. Starting in 2020, the US began flagging AVIC as a potential national security threat, imposing sanctions designed to hinder the growth of companies directly connected to China’s military.

“As the People’s Republic of China attempts to blur the lines between civil and military sectors, ‘knowing your supplier’ is critical,” then-Pentagon spokesman Jonathan Hoffman said in June 2020.

The Trump administration started a process that would see AVIC added to a suite of federal lists that variously restricted exports to the company and banned purchases or sales of publicly traded securities. The Biden administration continued and refined that effort, citing the “threat posed by the military-industrial complex” of China.

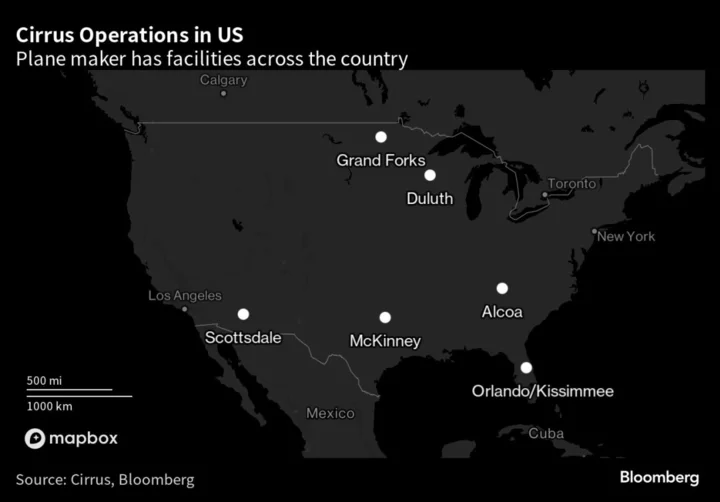

Throughout that period, Duluth, Minnesota-based Cirrus and other AVIC affiliates in the US continued to grow.

During the pandemic, Cirrus expanded its Duluth facility and opened a flight training center in Scottsdale, Arizona. Last year, Cirrus announced new sales, maintenance and training centers at two airports in central Florida, and in May the company flagged it had started construction of a $13 million facility in McKinney, Texas, near Dallas.

“We just love being able to brag that you are here in this city,” McKinney Mayor George Fuller said at the ground-breaking ceremony, according to Community Impact, a local news outlet. In a call with Bloomberg, Fuller praised the company’s investments, including the hiring of highly paid engineers.

In an emailed statement, Cirrus said it “has a policy of full compliance with US sanctions, export controls and other investment restrictions, including as it relates to our relationship with our parent company and as to sales in all 36 countries in which we conduct business.”

AVIC didn’t respond to questions about its ownership of Cirrus.

At a time of heightened sensitivities over Chinese-owned companies in the US, when some states have sought to restrict or ban Chinese investments, Cirrus isn’t the only AVIC-backed company winning praise from politicians.

AVIC is the largest shareholder, with about 46%, of Continental Aerospace Technologies Holding Ltd., which makes piston aircraft engines and components in Mobile, Alabama. Last year it received Republican Governor Kay Ivey’s “Trade Excellence Award” for its contributions to the state economy. Ivey’s office didn’t respond to questions about the company’s Chinese shareholder.

In 2022, Michigan gave more than $25 million in Covid-relief funds to Nexteer Automotive Group, an AVIC-affiliated maker of car parts based near Detroit that had about 12,600 employees and $3.8 billion in revenue.

None of those subsidiaries faces accusations of wrongdoing.

The debate over how best to apply sanctions comes amid bipartisan scrutiny of Chinese investments and a Biden administration effort to ramp up restrictions on technology exports to China.

During a trip to Beijing this month, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen said she emphasized to her counterparts that any measures would be “narrowly scoped” and clearly communicated. China has repeatedly said US restrictions are meant to stop the country’s rise.

With 2022 revenue of about $890 million, Cirrus is a small part of the AVIC empire. The state-owned group, which also makes commercial aircraft, has many closely-held subsidiaries as well as about two dozen affiliates traded in Hong Kong, China and Europe with a combined market capitalization of about $100 billion, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

One reason Cirrus and other AVIC companies have avoided sanctions has to do with how officials targeted the group: They never added it to the most restrictive sanctions list, which is overseen by the Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control.

Instead, Treasury created a new target list and said that list wouldn’t be subject to the department’s toughest restrictions, which would automatically apply sanctions to majority-owned subsidiaries.

“A lot of folks were scratching their heads a bit when the sanctions came out,” said Chase Kaniecki, who focuses on trade and national security issues as a partner at Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton in Washington.

The move likely reflected concern that some Chinese companies had subsidiaries all over the world, he said, and the US government didn’t want to impact them inadvertently.

The US made just such a misstep in 2018, when sanctions against Russian billionaire Oleg Deripaska resulted in an unintended spike in global aluminum prices.

Deripaska held a majority stake in United Co. Rusal International PJSC, at the time the world’s second-largest aluminum producer. Restrictions were never imposed on Rusal due to repeated waivers by Treasury, but the economic shock prompted a rethink on how the US should use its most powerful economic weapons.

In addition, some companies targeted for sanctions during the Trump administration successfully challenged the restrictions in court, and Biden’s team sought to bolster the legal justification for any listings.

AVIC, through its subsidiary China Aviation Industry General Aircraft, bought Cirrus more than a decade ago, when many American companies were struggling due to the Great Recession. The conglomerate spent around $210 million to acquire it, gaining access to small-plane manufacturing expertise.

The 2011 purchase was reviewed by the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States, a federal entity that can block foreign purchases of US companies and real estate, often on national security grounds. At the time however, US-China relations were less tense.

“There was a different risk tolerance,” said Emily Kilcrease, a senior fellow at the Center for a New American Security in Washington and former deputy assistant for foreign investment policy at the Office of the US Trade Representative.

Scrutiny on Cirrus could soon increase: The company’s prospectus with the Hong Kong stock exchange offers a look at its connections to other parts of the AVIC empire.

Cirrus Vice-Chairman Hui Wang is a director of AVIC Heavy Machinery Co., which is on one of Treasury’s sanctions lists and a Pentagon list of Chinese military companies. Another Cirrus director sits on the boards of two sanctioned AVIC subsidiaries.

The Hong Kong prospectus also says that since 2019, Cirrus has worked with AVIC-owned China Aviation Industry General Aircraft Zhejiang Institute Co. to make a training aircraft. The US in 2020 put that partner on a Commerce Department Military End User list, which means certain exports to it are restricted without a special license.

In its prospectus, Cirrus said it received US government approval for exports to China and has strictly complied with its export license from the Bureau of Industry and Security, an agency of the Commerce Department.

AVIC’s ownership isn’t an issue for Richard Kane, CEO of Verijet Holding Co., which leases point-to-point trips on Cirrus’s single-engine Vision Jet planes. Verijet, based near Miami, has about 20 Cirrus aircraft, which Kane praises as fuel efficient and safe.

“The Chinese have been pretty hands off,” Kane, who said he’s close to Cirrus’s management team, told Bloomberg. “So far, so good.”

But while there’s a big gap between producing general aviation, or GA, aircraft and weaponry such as AVIC’s sophisticated attack drones, the US subsidiary does potentially have expertise that could be valuable to military customers, said George Ferguson, senior aerospace and defense analyst with Bloomberg Intelligence.

“A small drone looks like a GA aircraft: small frames, long endurance, propeller driven,” said Ferguson. “It’s not totally without skills that are transferable.”

William Kim, a defense researcher at RAND Corp., agreed, saying that “while small private planes may lack military utility,” the technology that goes into them “could have some dual-use purposes.” He cited the use of composite materials in civilian planes and military drones as one example.

To build capabilities in small aircraft, AVIC would need access to the US market, Ferguson added, since restrictions on airspace use in China have kept the industry from developing there.

For now, sanctions experts say there’s probably little that policymakers can do about AVIC’s businesses in the US.

If it wanted to take a harsher approach, the government could attempt to force AVIC to divest its ownership of Cirrus and other US companies, just as the Trump administration tried to force Beijing-based ByteDance Ltd. to sell control of TikTok to a US buyer.

The US could also impose the most severe set of sanctions, putting AVIC on Treasury’s Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons List. That would block its assets and ban US persons from doing business with it, but it would be an extreme measure, the Center for a New American Security’s Kilcrease said.

“It’s a very big escalatory step,” she said. “If we are ever in a serious shooting war with China, you want to have that in your back pocket.”

--With assistance from Thomas Black, Isabel Webb Carey and Rebecca Choong Wilkins.