Astronomers have discovered four worlds unlike anything in our own solar system that provide a "missing link" between Earth twins and Neptune-like planets, they say.

The exoplanets have been labeled "mini Neptunes" — smaller and cooler than the easier-to-spot "hot Jupiters" found throughout the galaxy. They were detected using two space telescopes, one belonging to NASA and the other run by the European Space Agency and Switzerland.

Scientists are interested in mini Neptunes to learn more about the evolution of planets. Despite many other examples of them in the Milky Way orbiting stars other than the sun, these worlds still elude experts.

"We're not really sure what they're made of, or even how they formed," said Amy Tuson, one of the discoverers at the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom, in a video on the latest research.

SEE ALSO: The curious planets scientists have ogled in 2023, so farThe number of confirmed exoplanets has risen to 5,438, with 9,600 more candidates under review. Statistically speaking, the growing tally only scratches the surface of planets believed to be in space. With hundreds of billions of galaxies, the universe likely teems with many trillions of stars. And if most stars have one or more planets around them, that's an unfathomable number of hidden worlds.

The new worlds have been dubbed HD 22946 D, HIP 9618 C, HD 15906 C, and TOI-5678 B, with their discoveries published in four papers, two each in Astronomy & Astrophysics and Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Difference between super-Earths and mini Neptunes

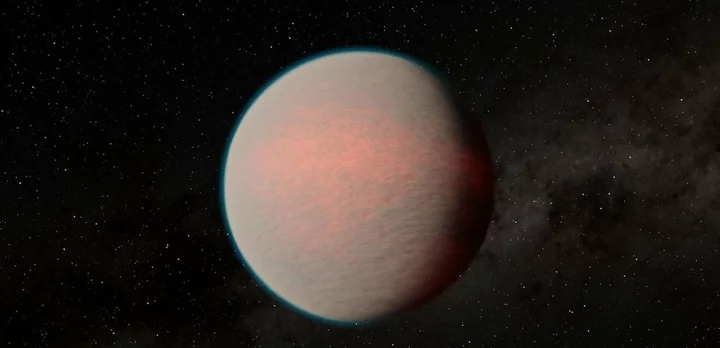

Mini Neptunes are mysterious worlds that are unlike anything found in our solar system. Credit: NASA / Adam Makarenko (Keck Observatory)Exoplanet hunters have coined names for different types of planets. Many of the known worlds travel in tight circles around their host stars. Smaller rocky planets are mostly divided into two groups, known as super-Earths and mini Neptunes. Although both kinds are larger than Earth and smaller than Neptune, super-Earths can be as much as 1.75 times the size of our home planet, and mini Neptunes are double to quadruple the size of Earth.

Usually, astronomers have a pretty good hunch about a planet's composition once they know its size and density. But that's not the case with mini Neptunes.

"They could either be rocky planets with a lot of gas, or planets rich in water and with a very steamy atmosphere," said Solene Ulmer-Moll, a researcher from the University of Geneva in Switzerland, in a statement.

If a mini Neptune has deep oceans with a water vapor atmosphere, it might have formed in the icy outskirts of its solar system before migrating inward; combinations of rock and gas might suggest the planet stayed in the place where it formed.

"We're not really sure what they're made of, or even how they formed."Want more science and tech news delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for Mashable's Light Speed newsletter today.

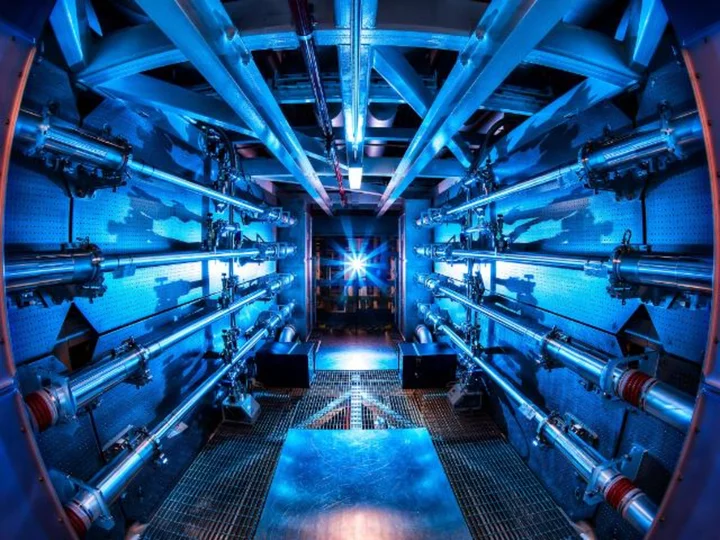

ESA’s exoplanet mission Cheops was used to confirm the existence of the planets. Credit: ESA / ATG medialab illustrationUsing TESS and Cheops to find exoplanets

The four exoplanets have orbits of 21 to 53 days around four different stars. That might seem short relative to Earth's 365 days, but not compared to the vast majority of known planets, scientists say, many of which are closer to their stars than Mercury is to the sun.

Their discovery adds to the growing sample of worlds with longer orbits around their host stars, more like the planets found in our own solar system. Being farther away allows them to have cooler temperatures. Some of the researchers involved in the detections said that could mean they're habitable.

NASA's TESS mission, short for Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, originally detected the exoplanets while they crossed in front of their stars. But because the U.S. satellite changes its view every 27 days, it isn't normally capable of witnessing planets whose orbits have longer periods with a second observation.

ESA’s exoplanet mission Cheops was used to confirm the existence of the planets. The satellite achieves this by observing when the brightness of a star slightly dims as a suspected planet passes in between its host star and our vantage point.

Cheops scientists have developed a method of predicting when a suspected planet will come back around to be more efficient about when and where it looks. Based on the technique, Hugh Osborn, an astrophysicist at the University of Bern in Switzerland, created software that proposes and prioritizes orbital time periods.

"We then play a sort of 'hide and seek' game with the planets," he said in a statement.