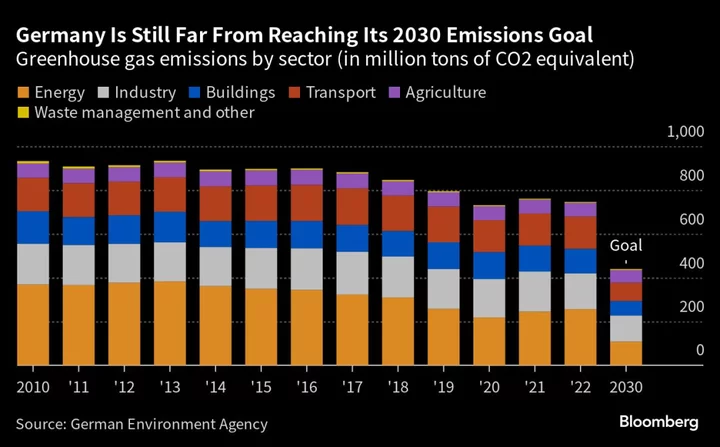

Even with one of the world’s most powerful green politicians in charge, Germany is failing on almost all its climate targets.

Vice Chancellor Robert Habeck — who’s responsible for energy and climate issues — has seen nearly every effort to reduce emissions this year fall prey to economic concerns or voter frustrations. The ruling coalition he forms part of is approaching its halftime mark having pledged hundreds of billions of euros to protect the environment, but it’s still badly behind on pledges to sink greenhouse gas pollutants.

Habeck himself has had to acknowledge that a goal to slash them by two thirds until 2030 compared to 1990 levels is likely to be missed by a significant amount — equivalent to about half of the UK’s emissions last year.

While the coalition — the first to include the Greens in almost two decades — has managed to push through policies that will bring the country closer to its aim, it has also faced substantial setbacks, including a diluted ban on fossil-fuel heating systems and intensified use of coal. Its slow progress jars with Germany’s efforts to convince China and other fossil-hungry countries to do more to protect the planet.

“With every softening, every constraint, the goal becomes even more unlikely to reach than it already was,” said Detlef Fischer, head of Bavaria’s energy and water industry association.

While energy and climate continue to be seen by voters as among Germany’s most important issues to address, public approval for the ruling parties has plummeted since the election in 2021. Meanwhile, the far-right, climate-skeptic AfD has gained popularity in recent state level elections, and other topics like migration have risen in importance for voters.

Energy

Germany accounts for a quarter of the European Union’s energy-related carbon-dioxide pollution, and about as much as its next largest emitters — Italy and Poland — produce together. That’s largely because of Germany’s manufacturing sector, which is heavily reliant on fossil fuels.

Simone Peter, head of the German Renewable Energy Federation, says the current coalition has done more to promote cleaner alternatives than any previous government. Wind and solar power output nearly doubled in the last 10 years, with particular gains in photovoltaics in the last two.

Still, energy continues to make up the largest share of the country’s emissions. Germany only plans to stop burning coal by 2038 — far later than most European peers, as efforts to move that date forward are currently stalling — and will intensify its use in power generation for a second winter to avoid shortages.

Ramping up cleaner alternatives — such as more wind and solar capacity, as well as new hydrogen-ready gas power plants — requires time and investments that some companies are currently unwilling to make, particularly amid higher borrowing costs. What is also “urgently needed” is an infrastructure that can properly transport and store this electricity, industry group DIHK said.

As a result, Germany’s goal to get 80% of its electricity from renewable sources by 2030, up from 48% last year, is “totally unrealistic”, says Graham Weale, an energy economist at the Ruhr-University Bochum.

Poland, by comparison, has not yet formally supported the EU’s pledge to be carbon neutral by 2050, but recorded the bloc’s largest emissions drop in 2022 as it cut coal use and became its fastest growing solar market.

Housing

Buildings in Germany account for a much smaller share of emissions than manufacturers, but many of them are old and poorly insulated, and about 75% of households are heated with gas or oil.

Habeck earlier this year proposed banning new fossil-fuel-reliant heating systems from 2024, a move which could have made a significant contribution to cutting emissions in the sector. But after months of public outcry over the costs associated with such a step, the measure had to be watered down, and is set to eradicate only about three quarters of the harmful emissions it initially targeted.

Clean-energy goals for municipal heating networks have also been rolled back, from an initial aim of 50% by 2030 to a more recent target of 30%. The coalition also shelved plans for tougher efficiency standards for new buildings amid a crisis in the construction sector and a housing shortage.

In contrast, the EU’s second biggest polluter Italy is on track to meet its 2030 targets — mainly thanks to a scheme that boosted the energy efficiency of buildings, according to the International Energy Agency.

Transport

While the government has at least presented strategies for the energy and housing sectors, the transport sector remains a key laggard. After a pandemic-related dip, road emissions have started creeping up again over the last two years.

The government did introduce a cheap nation-wide public transport ticket earlier this year to incentivize the switch from private vehicles. But recent estimates from the Association of German Transport Companies suggest it has only replaced about 5% of car journeys, and the group has argued that more needs to be done to expand public transport offerings in smaller towns and rural areas.

Many Germans continue to rely on combustion engine cars. But to reach the country’s climate targets, the stock of such vehicles needs to be reduced from 2025 at the latest, a step that currently seems “unlikely”, the German Council of Experts on Climate Change wrote in a report last November. It voiced concerns that old cars will continue to be used even if new electric vehicles are purchased.

Germany was also behind a push earlier this year to alter an EU-wide ban on sales of combustion engine cars post-2035. It lobbied for an exception for cars running on e-fuels, a usage which experts say is not energy-efficient.

At the same time, it’s not only individual policies that are likely to weigh on progress. Germany has also changed its overall strategy for reducing emissions, focusing on economy-wide goals rather than sectors. The new approach will make it easier for the dirtiest industries to get away with minimal changes so long as progress is made elsewhere, a step which was welcomed by the car industry at the time.

“As a rich, developed country with a historic responsibility, Germany still does too little,” said Hanna Fekete, co-founder of the New Climate Institute.

--With assistance from Maciej Martewicz and Alberto Brambilla.