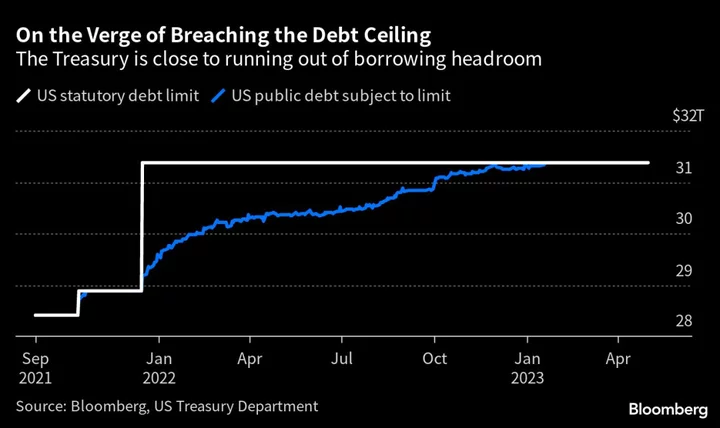

Investor concerns about the debt ceiling have ebbed now that lawmakers in Washington are pushing toward the finish line an in-principle deal struck by President Joe Biden and House Speaker Kevin McCarthy, but until everything is fully implemented the Treasury Department is maneuvering on the assumption that the government could still exhaust its borrowing authority.

Yields on Treasury bills maturing in the first half of June fell after a deal to avoid breaching the $31.4 trillion debt ceiling eased concern over the prospect of a calamitous US default. Bills due June 6 yielded 5.2%, down from more than 7% at one point last week. At the same time, the Treasury said on Tuesday it will continue paying down its stock of bills as it navigates around debt-ceiling issues ahead of legislation being finalized.

Meanwhile, the amount of money the US government has to pay its bills rebounded slightly at the end of last week, according to new data released Tuesday. The Treasury’s cash pile, which was at the lowest level since 2017, climbed on Friday to give the administration a little more breathing room under the statutory debt limit.

The White House and Republican congressional leaders geared up lobbying campaigns to win approval of the deal to avert a US default as environmentalists, defense hawks and conservative hard-liners condemned concessions. The debt-ceiling agreement would suspend the debt ceiling until Jan. 1, 2025, setting up a a fight in early 2025 over the tax cuts passed during the administration of former President Donald Trump, some of which expire after 2025, Stifel strategist Brian Gardner said in a note to clients.

From Washington to Wall Street, here’s what to watch to gauge how sentiment is shifting.

The Bills Curve

Investors have historically demanded higher yields on securities that are due to be repaid shortly after the US is seen as running out of borrowing capacity. That puts a lot of focus on the yield curve for bills — the shortest-dated Treasuries. Noticeable upward distortions in particular parts of the curve tend to suggest increased concern among investors that that’s the time the US might be at risk of default. That had been most prominent around early June, but yields on those maturities have eased since the Biden-McCarthy deal was announced, suggesting investors are less concerned about risks of missed payments.

The Cash Balance

The amount that sits in the US government’s checking account fluctuates daily depending on spending, tax receipts, debt repayments and the proceeds of new borrowing. If it gets too close to zero for the Treasury’s comfort could still be a problem until the legislation is passed. As of Friday there was close to $55 billion left, up from where it was the day before. Investors will be watching each new day’s release on that figure carefully. Focus is also on the so-called extraordinary measures that the Treasury is using to eke out its borrowing capacity. As of the middle of last week that was down to just $67 billion.

Insuring Against Default

Beyond T-bills, one other key area to watch for insight on debt-ceiling risks is what happens in credit-default swaps for the US government. Those instruments act as insurance for investors in cases of non-payment. The cost to insure US debt has retreated, but at one point it was higher than the bonds of many emerging markets that have credit ratings well below that of the US.

Rating Agencies

Hovering over the whole debt-ceiling fight, meanwhile, is the risk that one of the major global credit assessors might choose to change their views on the US sovereign rating. Fitch Ratings recently issued a warning that it could opt to cut the country’s top credit score, a market-roiling step that Standard & Poor’s took back during the 2011 debt-limit fight. This time around both S&P and Moody’s Investors Service have refrained from shifting their outlooks, although that is potentially a risk and investors will be clued in to anything that the major rating agencies might say about the situation, even if an agreement is concluded.