Wall Street strategists are divided on how much more the Treasury can expand its cache of bills, as concern rises about the cost of using more short-term debt to finance growing deficits.

The Treasury has sold about $1.56 trillion of bills on net this year through the end of September — and the bulk of that has come since the government suspended the debt ceiling in June. While strategists broadly agree that US officials will unveil another supply increase on Wednesday, tension is rising over the scale.

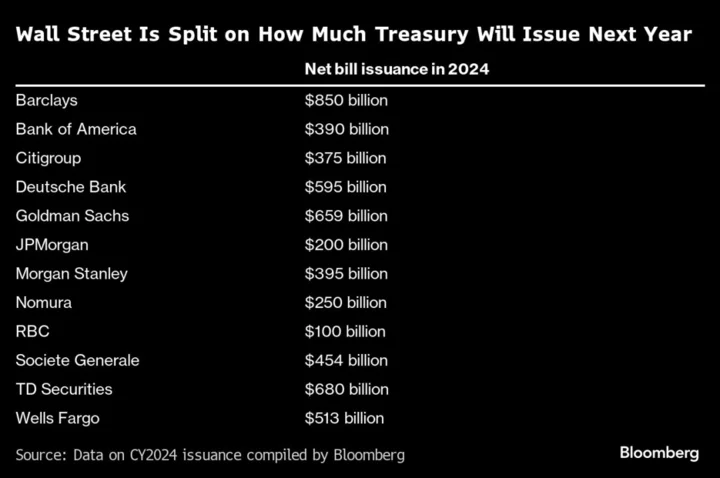

RBC Capital Markets sees only about $100 billion of net issuance next year. Barclays Plc, meanwhile, expects about $850 billion, while Jefferies LLC forecasts supply in 2024 closer to $1 trillion.

Forecasts have been complicated by uncertainty around when the Federal Reserve will finish unwinding its balance sheet, a process known as quantitative tightening, said Gennadiy Goldberg, head of US interest rates strategy at TD Securities, whose firm sees $680 billion of bill supply in 2024. The outlook for the federal deficit is also causing disparities, he said.

“It’s a bit difficult for Treasury to keep issuing bills,” Goldberg said, “because it exposes them to fluctuations in costs and also makes them overly exposed to front-end funding.”

The Treasury has flooded the market with bills over the past five months, finding ample appetite among investors who are attracted to 5%-plus yields. But that comes at a cost for the government, which faces greater rollover risk — or the potential that maturing debt is replaced with paper at higher yields — and a faster liquidity drain for the Fed.

The Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee — a group comprising dealers, investors and other stakeholders — has long recommended T-bills make up between 15% and 20% of total debt outstanding to help minimize rollover risk, while ensuring the securities are liquid enough. Outstanding bills made up about 20.4% of total debt at the end of September.

Even so, the committee said at the August quarterly refunding that it’s comfortable with short-dated obligations taking up a larger share.

There are liquidity challenges, however, with the Treasury running a structurally higher share of bills, according to Citigroup Inc. strategist Jason Williams. Citi forecasts the amount of bills outstanding will approach $5.6 trillion by year-end. That number could swell to $7 trillion or $8 trillion by the end of 2025 if the share of T-bills rises to 25% to 30%, potentially increasing rollover risk by about $100 billion, according to the firm.

A larger share of bills would mean that the size of the Treasury’s General Account — its account at the Fed — would have to be increased to $1 trillion to $1.2 trillion, according to Citi. Either bank reserves or balances at the reverse repurchase facility would therefore drain faster because the TGA is a liability on the Fed’s balance sheet.

Separately, a bigger share of bills and larger TGA would make it more difficult to navigate debt-ceiling episodes, when the Treasury is usually required to shrink its cash buffer in order maneuver under the limit.

Even as T-bills have been steadily cheapening since June in response to the flood of supply, investors have pulled more than $1 trillion from the Fed’s RRP in favor of an alternative to just parking cash at the central bank. But as usage approaches zero, the dwindling liquidity backstop risks pushing yields even higher, resulting in higher funding rates and widening swap spreads.

“There will be market impacts further down the curve from a deluge of bill supply,” Citi’s Williams wrote in a note. “There is no free lunch.”