Now that the twin strikes by Hollywood writers and actors are over, TV networks are scrambling to salvage the season that was supposed to start two months ago.

New and returning dramas and comedies typically debut on broadcast and cable in September and run until May. But the strikes, begun by writers six months ago and actors in July, largely prevented studios from creating new programs.

Because of that lost time, full-season orders for shows are getting shaved dramatically, with the networks planning to air fewer new series and fewer episodes of returning shows. And it’s all happening under the backdrop of weaker spending by advertisers and audiences shifting to streaming services.

Why Hollywood Actors and Writers Went On Strike: QuickTake

“It will make it half a season,” said Michael Nathanson, an analyst with MoffettNathanson. “But I think the damage has been done as viewers move on and so do ad buyers.”

TV legend Dick Wolf, for example, will be producing fewer episodes of hits such as Chicago Fire and Law & Order for Comcast Corp.’s NBCUniversal, according to people familiar with the matter. NBC has ordered 13 episodes of several Wolf shows, down from the usual 22, said the people, who asked not to be identified since the information isn’t public.

Walt Disney Co.’s ABC network is moving forward with new episodes of Grey’s Anatomy and The Rookie, trying to figure out how many they can squeeze in before NBA playoffs begin in April and advertising rates decline in June, according to people with knowledge of the matter.

Paramount Global’s CBS has been working through various models of how many episodes it will order of some 18 programs, including long-running hits like CSI: Crime Scene Investigation.

Ramping up Hollywood’s production machine won’t be quick. It’ll take at least six to 12 weeks to produce new episodes of broadcast shows, a schedule that will be hampered by Thanksgiving and the December holidays, according to TV agents and network insiders. A number of shows planned for the current season will likely be pushed to next fall.

Even though the writers came back to work in September, broadcast networks want to have three or four episodes done before putting shows on the air. That suggests viewers won’t see fresh content until February at the earliest. Generally speaking, half-hour comedies such as Fox Corp.’s Animal Control can be produced much faster than a one-hour drama like 9-1-1: Lone Star.

Delaying TV’s Emmy awards from September to their new date in January may help with promotion of the new shows, said Andrew Goldman, a former HBO executive and now adjunct professor at New York University.

“That has always been part of the machinery of getting the broadcast season back,” he said.

For new programs on streaming services, the wait may be even longer. Online giants often want to have a full slate of at least eight episodes completed so they can put them up all at once. Their programs can involve shoots in multiple cities and more elaborate sets, meaning it may be up to eight months before they can get fresh programming.

The last big TV writer’s strike, which ended in 2008, triggered a surge in reality TV shows, which don’t employ writers or actors. Similarly, these strikes have exacerbated trends that were already in place before the walkouts, such as cuts in the number of programs being produced.

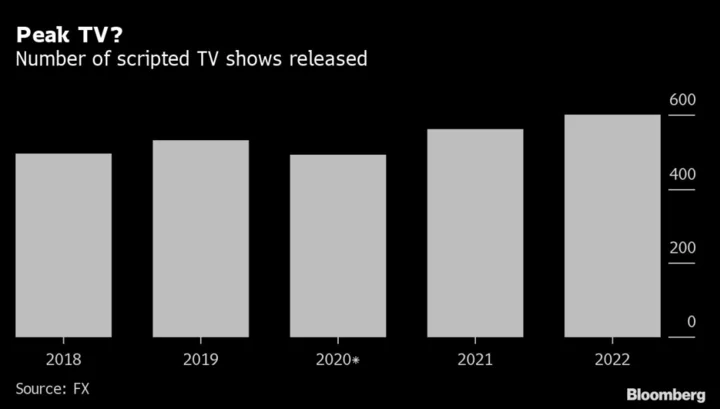

Industry insiders, like FX’s John Landgraf, speculated earlier this year that TV production likely peaked in 2022 at almost 600 scripted shows. Ongoing losses at streaming services, sliding advertising sales and cord-cutting by cable-TV customers have led to a sharp cut in spending. Some agents fear the number produced may be just 350 next year.

On a conference call with investors Wednesday, Disney executives said its spending on content, including sports, would be about $25 billion in 2024, down 17% from the level two years ago.

That means that even though the unions negotiated higher pay and other incentives as part of their new contracts, there still may be less money for all concerned. Writers have been returning to work with a smaller number of staffers on some shows, and sometimes at lower overall pay levels for top earners, as studios look to reduce costs by ending deals negotiated during the boom a few years ago, agents said.

Another trend that may not bode well for people working on new shows has been the success of reruns.

Netflix Inc.’s biggest hit last summer was Suits, a 12-year-old legal drama that previously aired on the USA network. Paramount, meanwhile, took its 5-year-old cable hit Yellowstone and put reruns on its flagship CBS network, generating viewer numbers comparable to some of the network’s regular shows. Going forward, the networks may continue to look for older series to air.

“For years in broadcast TV there’s always been structure, a fall season, a summer season, and everything was very rigid,” said Brad Adgate, a longtime industry analyst and advertising executive. “Now, they’re going to put on what they can.”

(Updates status of ABC shows in sixth paragraph.)