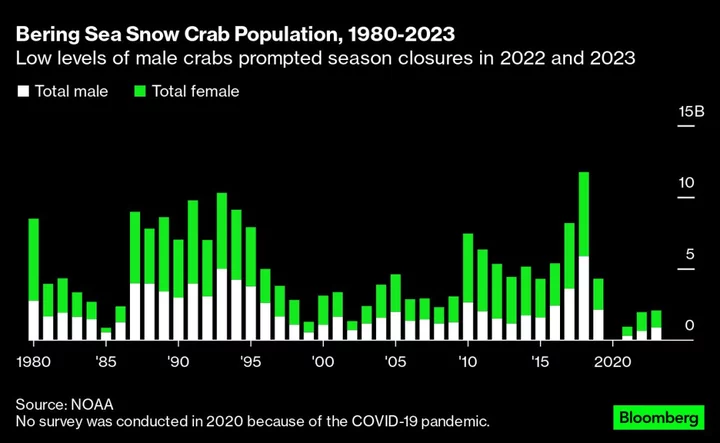

Alaskan officials recently canceled the Bering Sea snow crab season for the second year in a row — and the second time ever — due to dwindling crab population levels.

When researchers with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration surveyed the Bering Sea for crabs earlier this year, they recorded historically low numbers for both the big male snow crabs preferred by the fishing industry — defined as those with a carapace width of at least 102 millimeters — as well as mature female snow crabs. (Only male snow crabs with a carapace width of roughly 79 millimeters are allowed to be commercially caught in the region.) Commercial landings of Alaska snow crab, an iconic Alaskan export, totaled some 44 million pounds in 2021 and were valued at $219 million, according to NOAA data.

“The population is severely depressed,” said Ethan Nichols, assistant area management biologist at the Alaska Department of Fish and Game. The state agency announced the 2023/2024 Bering Sea snow crab season closure on Oct. 6. “I think what we’re seeing is just the continued effects of the initial population crash that we reacted to last year by closing the fishery for the first time,” he added.

Only a few years ago, in 2018, the Bering Sea snow crab population was thriving. Then marine heat waves struck the region that year and again in 2019, contributing to low sea-ice cover. Snow crab numbers started to drop after that.

Read More: Ocean Temperatures Hit 90 Degrees, Fueling Weather Disasters

Experts have surveyed the region for crabs every year dating back to the 1980s, but they skipped 2020 due to the Covid-19 pandemic. When researchers returned in 2021, they were shocked to find the area’s snow crab population had completely collapsed. Although there were enough large male crabs to support fishing that year, the continued drop in male crab numbers prompted officials to close the Bering Sea snow crab season for the first time in 2022.

Climate change and warming ocean waters likely played a role, although scientists are still figuring out the details. For example, some lab experiments suggest that warm ocean waters do not directly cause the Bering Sea snow crabs to die, explained Erin Fedewa, a NOAA fisheries biologist involved in the crab surveys. Instead, scientists hypothesize that the warming ocean temperatures are having an indirect impact on the crabs, perhaps by limiting their food access or making conditions more favorable for the spread of disease. Although many of the world’s oceans experienced record-hot temperatures this summer, Fedewa said the Bering Sea has so far avoided the high temperatures seen back in 2018 and 2019.

For the fishery managers and scientists tracking the snow crab’s decline, the 2023 survey results “really weren’t a surprise,” said Fedewa. Although levels of small male crabs seem to be rebounding slightly, it will take years for those crabs to grow into ones large enough to be fished, she explained, adding: “It’s going to get worse before it gets better.”

While the Bering Sea snow crab closure was disappointing to local crabbers, they did have other news to celebrate — the reopening of the Bristol Bay red king crab season in mid-October after two years of closures. Crabbers will be allowed to harvest 2.15 million pounds of red king crab this year.

“I’m glad it’s opening,” said Glenn Casto, a crabber and captain of the Pinnacle fishing vessel, in a statement released by the trade group Alaska Bering Sea Crabbers. “It will help pay some bills and most of all, it will help our crew out.”