The same day that Azerbaijan celebrated the surrender of separatist Armenian fighters in Nagorno-Karabakh, many in the breakaway region's capital spent the evening throwing stacks of paper onto a fire.

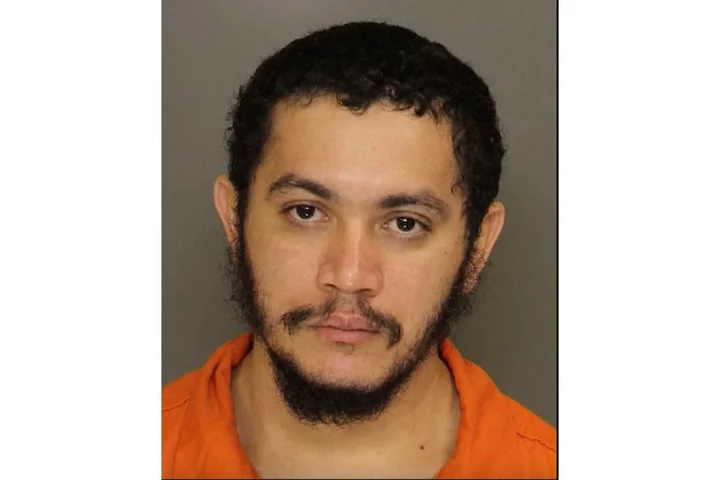

"One of the main things that people were doing in Stepanakert was burning all the possible documentation that could become evidence for the Azerbaijani authorities that they personally were part of the de facto government," Olesya Vartanyan, Crisis Group's senior analyst for the South Caucasus, told CNN.

"They believe that this could lead to their persecution," she said.

The ceasefire may have ended the latest brief but bloody conflict fought for control of the region, but there are fears a fresh humanitarian disaster is just beginning. Azerbaijan has said it plans to "reintegrate" Nagorno-Karabakh, but how this happens without a mass exodus of the region's more than 120,000 ethnic Armenians, or without violence being committed against those who stay and attempt to resist Azerbaijani rule, is unclear.

Azerbaijan said it had regained full control of Nagorno-Karabakh, an ethnic-Armenian enclave within its borders, after launching a lightning 24-hour assault on Tuesday that killed at least 200 people and injured many hundreds more. Karabakh officials said their forces were outnumbered and had no choice but to surrender.

Whether this leads to a lasting peace is not yet clear. Nagorno-Karabakh is internationally considered part of Azerbaijan but for decades has been under the control of Armenian separatists. Armenia and Azerbaijan have already fought two wars over Nagorno-Karabakh since the collapse of the Soviet Union, and ceasefire agreements between them have proven brittle.

While this ceasefire may have saved Karabakh from the sort of bloodbath seen in previous wars, it has utterly upended the lives of ethnic Armenians in the region, who now face an uncertain future. Whereas the 2020 ceasefire called on both sides to lay down their weapons, Wednesday's agreement was far more comprehensive. Nagorno-Karabakh's presidential office said it had agreed to the "complete disarmament of its armed forces."

But officials from Baku have demanded more, calling for "the dissolution of the puppet regime" in Nagorno-Karabakh, which has for decades been ruled by a de facto government not recognized by Azerbaijan or any other country, including Armenia.

Azerbaijan's President Ilham Aliyev has long been explicit about the choice that confronts Karabakh officials. In a speech delivered in May, he told Karabakh Armenians they needed to "bend their necks" and accept full integration into Azerbaijan. Baku sent representatives to meet with Karabakh officials in the city of Yevlakh on Thursday, "to discuss reintegration issues."

Few details were released about the meeting, ahead of which Aliyev said of the Karabakh Armenians that "all their rights will be guaranteed." The Azeri delegation said the talks had been "held in a constructive and positive environment," and had focused on the humanitarian situation, especially the need for fuel and food.

"Their requests were well received. The heating systems of kindergartens and schools, emergency medical aid and firefighting equipment, fuel and humanitarian aid will be supplied," the delegation said, according to the national news agency AZA.

There are fears over what "reintegration" entails, however. Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan and international experts have repeatedly warned of the risk of ethnic cleansing of Armenians in the enclave.

The United Nations secretary-general "remains deeply concerned about the impact of the escalation on the humanitarian situation," UN senior political official Miroslav Jenca said in a speech at the UN Security Council on Thursday.

Unable to leave

Nagorno-Karabakh has been under blockade for nine months. In December 2022, Azerbaijan-backed activists established a military checkpoint along the Lachin corridor, the only route connecting Armenia to the region, preventing the import of food and prompting fears that residents were being left to starve.

The blockade has also prevented humanitarian organizations and foreign media from accessing the region, meaning that it is difficult to independently verify reports of further Azerbaijani attacks and the movement of the Armenian population.

Siranush Sargsyan, a journalist in Nagorno-Karabakh, told CNN she could hear "intensive" shelling from a suburb in Stepanakert Thursday, while the negotiations between Karabakh and Baku officials were ongoing. "Most of the population were in panic, running and frightened," she said.

Following the truce, thousands of Karabakh residents reportedly fled to the airport, where Russian peacekeepers have a base.

Sargsyan also said "there are more than 20 villages under siege" in the more rural areas of Nagorno-Karabakh. "There is no electricity and phone connection doesn't operate, so we don't know if our relatives are safe."

Olesya Vartanyan said the movement of Azerbaijani troops into these areas displaced thousands. "These people, they don't have a place to live. Many of them are in the streets," she said.

While many Armenians, fearing further escalation, have already made up their minds to leave, Vartanyan said it is unclear who will organize routes out of the country, if the Lachin blockade is finally lifted. "Will it be Russian peacekeepers, the ICRC, or will it be Azerbaijani authorities?" she said.

"Then, does it mean people will have to go through filtration camps? And then will people get detained -- for example, the local men who took part in the fighting in the past, or those who were part of the local de facto authorities?" she asked. "It's a mess."

It is also unclear where Karabakh Armenians will travel to, if evacuations are able to begin.

"The Government of Armenia doesn't seek the displacement of the Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh and believes that the rights of Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh to live safely and in dignity in their homes must be guaranteed," Pashinyan's office told state media Armenpress Thursday. But, if this is "impossible, the necessary decisions will be taken," the statement added, without adding further details.

'This is my home'

Farid Shafiyev, chair of the Center of Analysis of International Relations in Baku, told CNN that the choice confronting Armenians who chose to stay was clear.

"Those who don't want to accept Azerbaijani jurisdiction, they have to leave. Those who would like to stay and get the passports, they are welcome to stay," said Shafiyev, whose center was involved in Baku's plans for "reintegration."

Asked whether she would also attempt to evacuate, Sargsyan said she wanted to stay in Stepanakert as long as possible. "But if they attack again I don't know what we will do," she said. "What I know is I can't trust them, their fake promises."

Beyond the immediate attempt to provide shelter and other aid to the thousands of Armenians attempting to flee Nagorno-Karabakh, there is the question of how Baku intends to dissolve existing institutions in the region and erect its own.

"This is an entity that has been self-governing as a de facto state. Prior to that it was part of Soviet Azerbaijan. It has a very long experience and practice of autonomy," Anna Ohanyan, a senior scholar in the Russia and Eurasia program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, told CNN.

Ohanyan warned that attempting to tear down existing institutions, which Baku has claimed it intends to, would be "an attack on the capacities for genuine peace-building down the road. If Azerbaijan was genuine about integrating, there would be some integration of these institutions."

More gravely, Ohanyan warned there is "no question" that Azerbaijan would use force, if Armenians in the enclave refused to accept Azerbaijani citizenship.

"If the Armenian community will not leave, but also will not take up Azerbaijani passports, I think that basically would be suicidal," Ohanyan told CNN.

The best case scenario, according to Ohanyan, would be "a Potemkin village... to continue to gaslight the West," referring to fake settlements once used to impress the Russian empress Catherine the Great.

"But in the long term, I think there will be a systematic push, continued demographic engineering to push Armenian communities outside the region."